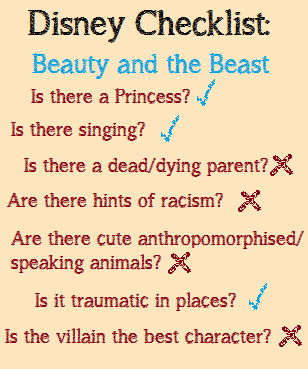

Part of the purpose of this blog is to treat animation with the same level of analysis and respect that live action cinema gets in many blogs, websites, magazines and newspapers. Too often animation is sectioned off by audiences and critics alike as for children, or a lesser medium, or somehow less relevant or powerful. Less review space is given to most animations except the biggest studio releases; previews and anticipation of animated films don’t reach the same levels as it does for the next blockbuster or big auteur release. They rarely play at the big festivals, let alone headlining them. This is a massive bug-bear of mine, as you might have guessed. However, every so often an animated film breaks out of its ghetto and crosses over into the realm of universally respected classic – the kind that appear on Best Ever lists and Most Important lists. In 1991, Beauty and the Beast was one of these films, an animated film seen by audiences around the world, raking in a gigantic box office critical adulation and, importantly, was nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars.

Part of the purpose of this blog is to treat animation with the same level of analysis and respect that live action cinema gets in many blogs, websites, magazines and newspapers. Too often animation is sectioned off by audiences and critics alike as for children, or a lesser medium, or somehow less relevant or powerful. Less review space is given to most animations except the biggest studio releases; previews and anticipation of animated films don’t reach the same levels as it does for the next blockbuster or big auteur release. They rarely play at the big festivals, let alone headlining them. This is a massive bug-bear of mine, as you might have guessed. However, every so often an animated film breaks out of its ghetto and crosses over into the realm of universally respected classic – the kind that appear on Best Ever lists and Most Important lists. In 1991, Beauty and the Beast was one of these films, an animated film seen by audiences around the world, raking in a gigantic box office critical adulation and, importantly, was nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars.

The Best Picture nomination – the first ever for an animated film, and still only one of three after they increased the number of candidates – was a massive milestone. It was almost an acknowledgement of surprise – one of the most universally loved films of the year was… an animation? It was beaten to the big prize by Silence of the Lambs, which swept the board that year. Nevertheless, Beauty and the Beast has stayed with audiences, and has the same enduring power as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, another crossover hit. Producer Don Hahn describes the production as a ‘perfect storm’ of people at the top of their games coming together to create a once-in-a-lifetime film – every person on it was essential, and would not have been the same without them. Many of the people that worked on it have gone on to direct – the story department alone included Chris Sanders (Lilo and Stitch, How to Train Your Dragon), Brenda Chapman (Prince of Egypt, Brave), Roger Allers (The Lion King) among many others. Buoyed by the success of The Little Mermaid, this was a studio and crew at the very top of their game creating unforgettable cinema. This serendipitous collaboration of talents caused the film world to pay attention to animation once again and rightly so – Beauty and the Beast is a triumphant, gorgeous, emotional masterpiece and I use that word with no reservations and no fear of hyperbole.

The reason it is so successful is that it is technically impressive both as a story and animation, but is also thematically and emotionally satisfying. To start with the former point, the most immediately obvious achievement is the standard of animation. Beauty starts with a series of images in the style of stained glass windows (more on that later), functioning as a return to the most basic forms of visual storytelling before transitioning to a state of the art blend of hand drawn and CG animation. The integration between the two styles here is far smoother than in films like Basil or even Aladdin, which followed on from it. The initial provincial town that Belle wants to escape from, as well as the exteriors of the castle and the principal characters, are all animated beautifully using traditional techniques, placing Beauty and the Beast firmly in the realm of the fairy tale – the soft colours of the backgrounds recall Snow White and Cinderella, while Beast’s iconic castle gives everything an enchanted air. CG is then introduced, subtly, when the scene calls for grandeur – most notably in musical numbers and in the legendary ballroom scene. The resulting aesthetic is one that manages to impress you with its scale and opulence at the same time as captivating you with an intimate, magical atmosphere. It’s a piece of escapism, rooted firmly in fantasy; in short, it looks exactly like the fairy tale of a thousand childhood imaginations.

Accompanying the stunning animation is Alan Menken’s finest work as a composer. The songs are obviously incredible (more on them later), but the score that runs throughout is just as impressive. The stained glass opening is so memorable partly because of Menken’s spin on Saint-Saens’ famous Aquarium segment of his Carnival of The Animals. There’s something haunting about the high, twinkling motif that opens the film and recurs throughout, conveying the melancholy behind the magic of the story; the castle may be enchanted, but at the cost of the freedom of the people who lived there. It’s a deeply romantic theme but, fittingly for the character of Beast, tragic as well. Every plot point is matched, beat for beat, by the score. It is as romantic and dramatic and comical as the film requires, and contributes once more to the mystical appeal of the film.

Structurally, Beauty is impressive, too, packing in quite a lengthy story into a tightly written 84 minute film. The audience is asked to buy into a relationship that goes from fear, to anger, to love over the course of its running time, and miraculously it achieves this. Where many a fairy tale romance is trite, only there because it is expected to be, the growing romance between Belle and captor is more credible – and also far more complex than some ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ jokers would imply. The opening song perfectly captures Belle as a character (more on her later), and her resentment of the simplicity of her provincial home: her fellow townspeople are banal, dim or leery. So it quickly establishes that she is seeking adventure, something a bit different, and someone who shows more compassion and interest in her beyond her looks, so that when she finds all this in Beast and his castle, it is not difficult to believe that she might fall for him in spite of his initial temper and bad decision making. The rest plays out as a series of moments interspersed with songs, culminating in the ballroom scene. We don’t see every minute of their blossoming romance, but we see the important ones, making Beauty and the Beast one of the most believable and moving of any Disney couple. If there has to be boy-meets-girl story, at least make it as good as this one.

Which leads to the second reason for the success of this film: it is emotionally and thematically satisfying. Part of this is down to a collection of cleverly written characters. Gaston is a complex villain for children to get their heads around because he isn’t obviously evil in the way that Cruella De Vil wants to skin puppies, or that Maleficent has horns and green skin. He’s someone that, in another film, could be the Prince Charming character. At first he is just an arrogant doofus and has no grand plan or evil scheme – he just lets his arrogance and need for control take over until his own stupidity leads to him plunging to his death. Beast, a more obvious villain character, cuts a terrifying figure, often in silhouette at first, as he storms around the castle – yet the loyalty of his staff, even though he is responsible for their curse, hint early on that there is more to him than meets the eye. The transformation at the end into a bland, long haired fop slightly betrays the character transformation he has already undergone; becoming good looking is merely a footnote to the far more interesting story that it marks the climax of. Then there is Belle, seen as an oddball because she reads lots of books and isn’t interested in men. She’s a fantastic heroine, and her cry of ‘I want adventure in the great wide open’ is one that speaks to a far wider audience than ‘some day my prince will come.’

With these two fascinating characters at the centre, the script teases out a number of familiar but fascinating themes, which again show the complexity of the central relationship beyond falling in love. There’s the obvious theme captured even in the title, that our initial perceptions of people often betray us. Belle’s love of books is a charming trait, but it also builds up expectations of being swept away by a man, hence her confession in a song ‘true, that he’s no Prince Charming.’ She is aware of fairy tales, and almost expects to be in one, but has to overcome her ideas about what a Prince Charming might look like before she falls for hers. Beast, too, has to change his ideas about love to the extent where his ultimate redemption comes from the symbolic act of letting Belle leave to find her father. Their relationship is built on meeting each other half way, of letting their guard down and being prepared to change. In contrast, the small mindedness of the townspeople is what leads to them attacking the castle. ‘We don’t like what we don’t understand, in fact it scares us,’ they all sing as they brandish flaming torches and march to kill the Beast. Extrapolating from that, one wonders if Howard Ashman, who wrote the lyric and was openly gay, was deliberately giving a tale as old as time a more pointed relevance to the time it was released. This is a film that champions being open minded and criticises ignorance.

Yet it’s not just another ‘look beyond the surface’ story (although that is a favourite theme of 90s Disney, cf Aladdin, Hunchback), as the writers also weave in themes of sacrifice and freedom. Love, in different forms, is shown by sacrifice throughout the film – Beast is first drawn to Belle because she is prepared to give up her freedom to save her father. This magnanimous act is later reflected and inverted in Beast releasing her to go, once more, and save Maurice. Both make huge sacrifices out of love, and Belle’s substitutional imprisonment feels particularly powerful: not only does it make her an active, not passive, participant in her story, but it rings with a spiritual truth that the greatest love is known in giving up your life for someone else.

It is these sacrifices that ultimately lead to freedom, another preoccupation of the film. Most characters are imprisoned in one way or another: Belle and Maurice by the Beast; the staff are trapped by a curse; the people are imprisoned by their own ignorance, unwilling to think outside the box or leave their simple town; even Le Fou is kept in a kind of voluntary servitude to Gaston. Yet freedom comes for the characters when love through sacrifice is shown. When Beast roars into the night sky in anguish as Belle rides away from the castle, he hasn’t just let the person he loves leave him, he has given up his chance to become human again and effectively condemned himself to life as a monster. Yet this act of love is what eventually brings Belle back to him and frees the castle from the witch’s curse. Freedom comes at a cost, but one, perhaps, worth paying.

What all this ultimately adds up to is a film that resounds with emotion in the way that only the best stories can. The songs, written by the legendary Howard Ashman before his untimely death in 1991, are lyrically witty and emotive, each one telling a story in a way that you couldn’t get away with if it was merely spoken. There’s the fabulous ‘Be Our Guest,’ which fits into the great Broadway tradition as I discussed in my article on The Little Mermaid, and ‘Kill The Beast’ which throws in references to 20s musicians and Shakespeare. Each song acts as mood-setter, expressing the emotional developments of the film in a way that is both simple and effective. The highlight is, of course, the ballroom scene, the culmination of a relationship that has been building up to this grand romantic gesture. As the unlikely pair waltz gracefully around the golden dancefloor, and Mrs Potts warbles the line ‘Bittersweet and strange / finding you can change / learning you were wrong,’ this most unbelievable of stories aims straight for the heart and hits with unnerving accuracy. It’s the kind of song and thus, the kind of film (and consequently, this article) that has no room for cynicism. This is unabashed escapist romance, and it does it beautifully.

Beauty and the Beast, therefore, is a total triumph for Disney, a stunningly told story that resonates with universal themes of love, sacrifice and freedom. It is no wonder that audiences, critics and awards boards alike responded so enthusiastically to it, and that people continue to return to it today. It’s a stunningly executed film, one that has the power to speak to people of any age if you let yourself be drawn in by its spell. Which is impressive in any medium, but it should prove once and for all that animation is capable of achieving all these things and more. In short, films like Beauty and the Beast essentially justify the existence of this blog. Here’s the thing: it’s not even my favourite from this period, so if you thought this article was over the top, wait til you read my review of The Lion King.

Astute readers of the #Disney52 project will have picked up that I actually quite liked the films of the period I called The Obscure Eighties. They are fun, strange and just a little bit different to the Disney you might be more familiar with. However, the release of The Little Mermaid in 1989 was greeted with critical fanfares and a gigantic box office. Something had clearly changed for the House of Mouse, and although their next film, The Rescuers Down Under, was a financial flop, their next films – Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and The Lion King – were huge hits, earning the period from 1989-1994 the title of ‘The Second Golden Age’. This is a lofty title, as it harks back to their first films, each one a wondrous, beautifully animated, heartfelt film with some of their best loved stories. Can the films of this era really be as good as their earliest work? And what separates these from their films of the 80s, which in hindsight are really not bad? The answer to both of these lies in The Little Mermaid, the film that changed everything.

Astute readers of the #Disney52 project will have picked up that I actually quite liked the films of the period I called The Obscure Eighties. They are fun, strange and just a little bit different to the Disney you might be more familiar with. However, the release of The Little Mermaid in 1989 was greeted with critical fanfares and a gigantic box office. Something had clearly changed for the House of Mouse, and although their next film, The Rescuers Down Under, was a financial flop, their next films – Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and The Lion King – were huge hits, earning the period from 1989-1994 the title of ‘The Second Golden Age’. This is a lofty title, as it harks back to their first films, each one a wondrous, beautifully animated, heartfelt film with some of their best loved stories. Can the films of this era really be as good as their earliest work? And what separates these from their films of the 80s, which in hindsight are really not bad? The answer to both of these lies in The Little Mermaid, the film that changed everything.

To answer the second question first, the key separating factor between The Second Golden Age films and those of the eighties is spectacle. The Fox and the Hound – arguably the strongest of the 80s films – is an emotive, involving story that can very easily bring an audience to tears, but it is undeniably small. Perhaps due to budget constraints, the film is more of an intimate character drama than the epics and romances of the 90s. Basil the Great Mouse Detective has some great action but is sparsely detailed and, again, feels small in comparison. Even the high fantasy of The Black Cauldron and the New York setting of Oliver and Company seem to be curiously restrained, the animation reigned in and the action limited to just a few moving characters and undetailed backgrounds. Whilst this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, the Eighties are undeniably scaled back, cheaper and slighter than the films that followed.

The Little Mermaid, however, is a different kettle of fish. The animators threw everything at the screen, buoyed by the relative successes of Oliver and Basil, and the results are spectacular. Take, for instance, the legendary song ‘Under The Sea,’ part of a fantastic soundtrack by Broadway writers Alan Menken and Howard Ashman (who tragically died after working on Beauty and the Beast). The theatrical sensibilities of Ashman and Menken affected not only this film but its successors, too – there would be no ‘Prince Ali’ or ‘Be Our Guest’ without this Caribbean tribute to life underwater. It’s not just in the songwriting, however, but the idea of putting on a show, that is brought in from the stage to the screen, and ‘Under The Sea’ is certainly a show. It starts off with Sebastian the Jamaican crab singing just to Ariel, but over the course of the song he enlists the help of all the denizens of the deep. Each kind of fish is used to recreate an instrument, and the more colourful creatures create patterns like a floating dancing troupe. Like the best Disney songs, the accompanying images are inventive, colourful and energetic. Crucially, the frame is full during this sequence, one detail that separates it from earlier films. The Broadway Musical mindset gives the action in the song a sense of escalation, so the increasing number of aquatic dancers means that eventually the screen is packed with images of underwater antics. The sense of spectacle shown in this sequence is a key feature of Second Golden Age cinema, and is no doubt one of the main attractions to the audiences that watched and rewatched The Little Mermaid endlessly on its release in 1989.

Crucially, in spite of this spectacle, The Little Mermaid maintains the strongest element of the eighties films: character. Where previous fairy tale films were about the supporting characters – dwarfs, mice or fairies – here Ariel is front and centre with the secondary cast being just that. The role of Ariel is, however, a contentious one, as the loss of her voice as a trade off for legs is arguably as neutering to the character as a loss of consciousness is to Aurora in Sleeping Beauty. I would argue, however, that she shows a strength the likes of which Snow White, Aurora and Cinderella could never dream of mustering. Firstly, her desire to be a human is not dictated by her love of a man. ‘Part Of Your World,’ Ariel’s musical lament about wanting to live on the surface, appears before she has even set eyes on Eric. This means that unlike her predecessors, Ariel has established a character before she encounters a man; she is curious, defiant, fearless and a bit different to the rest of her family. Eric is merely the catalyst that prompts Ariel to make the terrible decision to give up her voice in exchange for her lifelong dream of living as a human. Even when on the land, Eric doesn’t quite fall for her, it’s a memory of her singing that is holding him back. As the voice is such a powerful symbol of freedom and character, it’s telling that Ariel requires it as much as she needs legs to fully exist as a human, and to realise her love. Clearly, then, there is far more to Ariel than the standard Princess arc of ‘meets man, marries man’ – she’s an interesting, lively character that marks a welcome break from traditional Disney princesses.

This combination of spectacle and characters, then, answers the first question – are the Second Golden Age films worthy of comparison to the magnificent Snow White, Fantasia et al? On the strength of The Little Mermaid, the answer is a resounding yes. It’s an impressive film on almost every level: it’s funny, and even throwaway scenes such as Sebastian trying to avoid being cooked, are brimming with wit and ingenuity; it’s visually magnificent, returning to the awe and wonder of Disney’s earlier films and creating whatever the mind of man can conceive. There’s drama, too, featuring the tensest romantic boat ride ever and a thunderous maelstrom of a finale. Most importantly, with Ariel at the centre of the film, The Little Mermaid has heart, and lots of it. This isn’t just better than the films of the ’80s, it’s a league above them, representative of a studio that had finally got its verve back and was revelling once more in all that animation could offer. It’s a breath of fresh, seawater air to a studio that, although still making smaller, decent films, really needed it to survive.

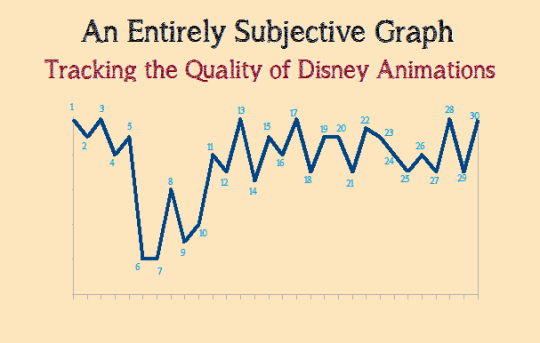

There is no graph this week as I’m away from home and I have all the stuff stored for it on my desktop. Sorry!