The kids I took to see Big Hero 6 were convinced that the film was actually called Baymax. It’s easy to see the confusion: all the marketing has focussed on the big marshmallow-esque robot, and the film sort of does, too. The implied team of the film’s title feature, but at the end of the day, there is one thing that everyone, children and adults alike, will remember from Disney Animation’s latest, and that is the studio’s greatest animated character of their CG era.

The friendly healthcare robot was designed by Todashi, the brother of the prodigiously talented and subtly named Hiro. When Todashi dies in a tragic accident, and a villain starts to roam the streets of San Fransokyo, Hiro, Baymax and their science-genius friends form the titular group to defeat the mysterious masked man and find out what really happened to Todashi. As plots go, it’s fairly uninspiring, the central mystery having been likened by some critics – not unfairly – to an episode of Scooby Doo. The big finale, where the whole team work together and use their tech to intelligently battle a billion tiny bots, would not feel out of place on a Saturday morning cartoon, either; it’s a fairly disposable Disney denouement.

Except for when Baymax is involved.

There is much to admire about the film aside from Iron Man’s cuddly cousin. Where many superhero films are content to let thousands of civilians die and have whole cities erased for the sake of a BIG final act – ironically making them all uninteresting and indistinguishable from one another – Big Hero 6 is a superhero film with almost zero collateral damage. The team focus their skills and technology on protection, not violence, and this emphasis is crucial and refreshingly different. The animation is impressive, too, rendering the hybrid city of San Fransokyo in vivid colours that would make Christopher Nolan tut in disapproval. The whole film is just a lot of bright fun, and goes some way to restoring a light touch to the tired and serious superhero subgenre.

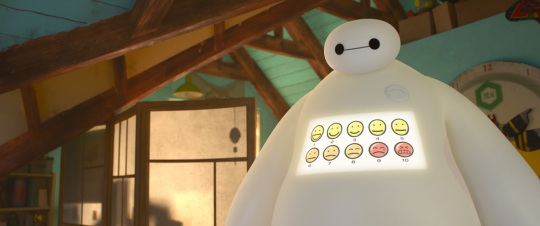

It is, however, all about Baymax. You are probably already familiar with his look: white airbags; a low centre of gravity; a face like an emoji. It’s a beautifully minimalistic piece of character design, making the most of Disney’s age old animation principle of Squash and Stretch (exactly what it sounds like), while maximising one of their other twelve principles, Appeal (the idea that every character should be animated in a way that appeals to an audience), simply through its movement. It’s textbook stuff – literally, in that the principles are laid out in The Illusion of Life, as close as Disney gets to a textbook – used since Snow White but here being applied with equally cutting edge technology. From the way that he waddles along, even when in a dramatic chase, to the way the tilt of his bulbous head can evoke emotions, Baymax shows that Disney are still masters of character animation, and that no matter how new and shiny your programmes are, you still have to use them well.

Baymax is more than just an object lesson in how to animate a character, he‘s also a perfect example of how to use character to explore themes in interesting and new ways. Grief and loss are weighty topics for a kids‘ film to tackle, but also important ones; kids all have to confront death for the first time at some point in their lives, so using cinema to explore that is a great idea. The first act gives Todashi enough screen time to really make his death felt by the audience, and the rest of the film is about coping with that loss. The directors use Baymax to explore this by the literal-thinking robot seeing Hiro’s sadness as something that can be cured and so the internal process of Hiro’s grief is externalised in a deft manner, managing to be light-hearted and funny without ever detracting from the seriousness of the topic. The themes are, therefore, inextricable from the two characters at the centre of the story.

The result is a character who, in a Disney film in the early ‘00s would have been a comedy sidekick, is now the emotional heart of the film. It’s a such a simple but effective concept it’s amazing it hasn’t been done that much before (something like Robot and Frank is the closest comparison). The finale only transcends its familiarity when it focuses on the relationship between Baymax and Hiro, and creates something special. Big Hero 6 as a whole, while a lot of fun, will not go down as one of the studio’s revered classics, but Baymax will be remembered as one of their greatest creations.

smilingldsgirl

Great review. I totally agree about Baymax. He was kind of the love of a brother in physical form. It really moved me. Reminded me of Up in the way a character’s presence is felt throughout the whole film.

I also liked that the team was diverse with different races, women, men ect. That makes me excited for what they can do in the future. And Sanfransokyo was so creative. There were some predictable elements but every genre has those boxes you have to check off. It’s neat to hear the perspective of a Dad. Thanks!