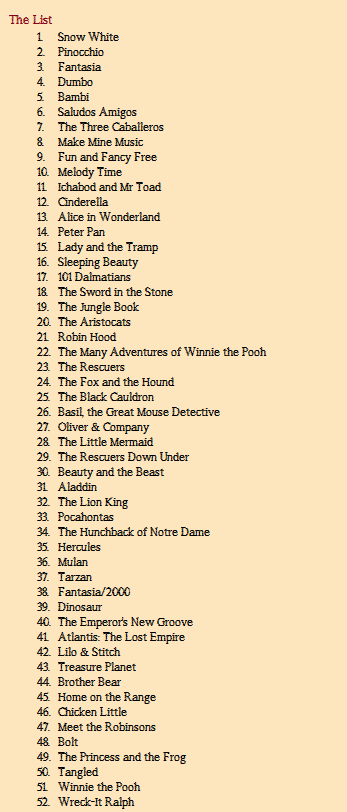

Winnie the Pooh seems to be forgotten about in the UK. For some time now, Disney have been putting the number of the classic on the side of DVDs and Blu-Rays. These numbers correspond with when they were released in cinemas and I’ve been following that order for this very project, right up until No.50, Tangled. Number 51, according to the sides of boxes in the UK, however, is Wreck-It Ralph. A confusing blip, as most other sources list Winnie as 51 and Ralph as 52, hence the idea of the project to watch 52 in a year, one a week (though I hardly stuck to that by the end). Yet Winnie the Pooh was undoubtedly made by Walt Disney animation studios and it DID have a theatrical release over here. So why the decision to leave it out of the canon? It’s perhaps a triviality but for an obsessive like myself it’s disconcerting. Will all future Disneys in the UK be one number behind? Perhaps Disney were embarrassed by Pooh, although that hardly seems likely as the film is a charming, child friendly ramble through the Hundred Acre Wood.

Winnie the Pooh seems to be forgotten about in the UK. For some time now, Disney have been putting the number of the classic on the side of DVDs and Blu-Rays. These numbers correspond with when they were released in cinemas and I’ve been following that order for this very project, right up until No.50, Tangled. Number 51, according to the sides of boxes in the UK, however, is Wreck-It Ralph. A confusing blip, as most other sources list Winnie as 51 and Ralph as 52, hence the idea of the project to watch 52 in a year, one a week (though I hardly stuck to that by the end). Yet Winnie the Pooh was undoubtedly made by Walt Disney animation studios and it DID have a theatrical release over here. So why the decision to leave it out of the canon? It’s perhaps a triviality but for an obsessive like myself it’s disconcerting. Will all future Disneys in the UK be one number behind? Perhaps Disney were embarrassed by Pooh, although that hardly seems likely as the film is a charming, child friendly ramble through the Hundred Acre Wood.

Admittedly, the two Winnie the Pooh films are a bit of an oddity in the canon, stylistically and tonally incongruous with the the other fifty. A.A. Milne’s unique brand of whimsy does not translate to gripping adventures or heartfelt fairy tales, instead creating films where the sum total of incident is a stuffed donkey losing its tail and some other toys getting trapped down a hole while they try and catch an imaginary creature. Yet this resolutely gentle style of storytelling means that the charm of the Pooh films is quite unique to these two adaptations. They’re funny without forcing it, quirky without trying and beautifully, inventively animated.

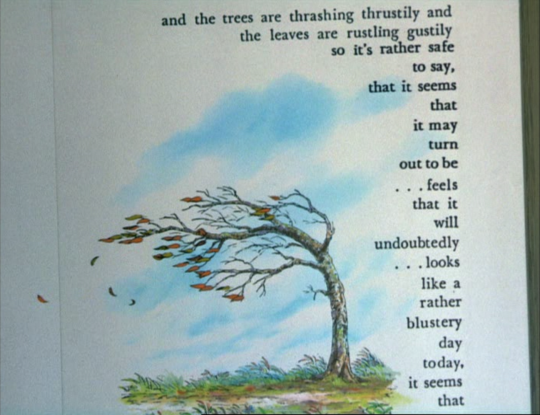

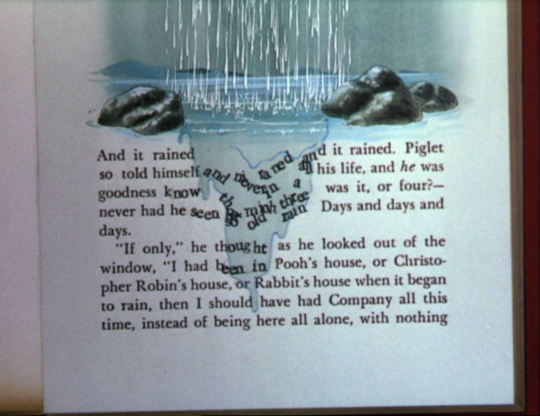

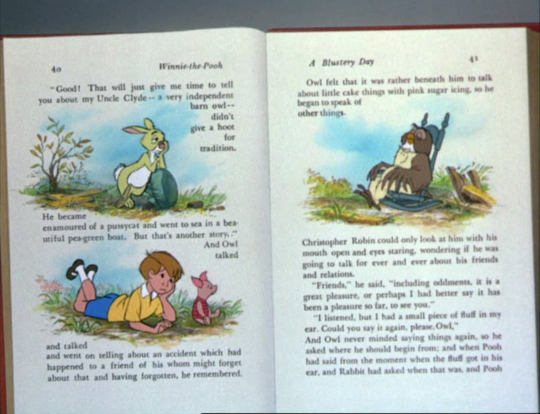

The 2011 edition doesn’t add much to Wolfgang Reitherman’s superior 1977 film The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, but it reuses the meta stylings of that children’s masterpiece often to great effect. By borrowing from brilliance this, too, hints at such invention and wit. Pooh once more interacts with the narrator (here John Cleese on fine form) and occasionally stumbles out of the illustrated sections of his book, and the writing is again affected by the events of the narrative. Words are dragged or blown or fall into the story, and the characters have even more fun with them this time. At one point, they even become a crucial plot point to help the stranded heroes. Such playfulness is always a joy to watch, and it used brilliantly in this second Pooh film.

The animation is once again unshowily beautiful, the backgrounds in particular looking a lot like Shepard’s line drawings. The colours seem to be a bit brighter this time, and the character animation is bolder and clearer than in the ’77 film, but this still looks as though it were made in a different era. It’s as far a cry from the lush lighting and immaculately detailed CG of Tangled as you can imagine from Disney, once again showing that this film feels out of place at Disney. This truly seems to be the last hand drawn film from the studio, a quietly brilliant tribute to the beauty of the medium, showcasing its capacity for invention and atmosphere even as it dies to the onward march of pixellated progress.

The only thing that feels modern about Winnie the Pooh is that the voice cast is noticeably different to the older, familiar voices of The Many Adventures. Put quite bluntly, they are just not as good, voice acting veteran Jim Cummings no match as Pooh compared to the inimitable Sterling Holloway. Bud Luckey’s attempt at Eeyore is disastrous, and the sense of the cast as a whole is that they don’t quite gel in the same way. The less said about Zooey Deschanel’s songs the better.

Winnie the Pooh feels like a small, independent production and a far cry from the studio that made hyper-slick films like Tangled and Wreck-It Ralph. It’s a low key, rusty film that moves at a different pace to everything else that Disney makes. As such, it’s sure to gain a devoted audience of young fans (and a few older ones, too), but it perhaps explains why Disney were not so keen to acknowledge it as part of their canon of classics. It’s a shame, however, that this is excluded when Saludos Amigos isn’t, as this is a happy, charming film full of gentle delights.

Adventure. ad.ven.ture. /adˈvenCHər/ Noun: An unusual and exciting, typically hazardous, experience or activity. Verb: Engage in hazardous and exciting activity, esp. the exploration of unknown territory: “they had adventured into the forest”.

Adventure. ad.ven.ture. /adˈvenCHər/ Noun: An unusual and exciting, typically hazardous, experience or activity. Verb: Engage in hazardous and exciting activity, esp. the exploration of unknown territory: “they had adventured into the forest”.

Wolfgang Reitherman’s films could very legitimately be described as adventures: 101 Dalmatians sees a group of puppies fleeing an evil fur lover; The Jungle Book is about a boy surviving in an environment full of predators and orangutans; Robin Hood is about Robin freakin’ Hood. Yet the extent of adventures in his penultimate film, The Many Adventures of Winnie The Pooh, is a quest to get some honey, getting slightly lost in some woods and a particularly windy day. There is no peril, no hazardous activity and no exploration of note. The closest they get to unknown territory is when Pooh is trying to track a creature in the snow… the creature turns out to be him. So the title is something of a misnomer, and Reitherman’s final film, The Rescuers, packs in far more adventure in its credits sequence alone than this has in the whole film.

That is exactly what makes The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh such a charming, delightful film. It has the kind of wonderful whimsy and childish imagination that makes films like My Neighbour Totoro so beloved, and it has a similar episodic narrative to Ghibli’s greatest masterpiece, too. As plots go, Pooh’s persistent honey hunt is hardly gripping, and a violent rainstorm doesn’t class as adventure in the traditional sense. What makes the film so appealing is that Pooh, Reitherman and, consequently, the audience view all these minor events as adventures nevertheless. In the Hundred Acre Wood, everything new is unusual and exciting, and even a day out in the snow becomes a hazardous experience or activity. This naivety lends the whole film a sense of wonder, and takes you on as much of a journey as The Rescuers or The Aristocats does, even if it never leaves the confines of a map drawn by A.A. Milne and E.H. Shepard.

Shepard is a key figure in the charm of The Many Adventures. The legendary illustrator responsible for many of the iconic images associated with Milne’s great books and Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows is clearly a huge influence on the look of Reitherman’s adaptation. Whilst the character design is a much more ‘Disneyfied’ than Shepard’s drawings, the landscapes and backgrounds are straight out of Shepard’s illustrations. Two things stand about the animation style that feel Shepardian. Firstly, the clearly hand drawn lines and sketched details, such as the lines of bark on trees, give the film a storybook feel even when it isn’t clearly shown as such. Secondly the use of blank spaces in some of the wider shots are a perfect match of Shepard and Reitherman’s aesthetic styles, where the lack of detail lends the film an imaginative, unrealistic beauty in which the world of the story doesn’t seem to exist outside the frame of the film, or the diegesis. These two elements place the film purely in the realm of fantasy – the perfect arena for Pooh’s many adventures.

The animation perfectly serves the lovable characters and sweetly realised world. The Hundred Acre Wood is the kind of place where no sign is spelt correctly and the wood is inhabited by bears, rabbits, kangaroos and tiggers. Each of Milne’s characters come across well on screen, with Pooh, a bear of little brain, forming the dimwitted, gentle and occasionally self-centred hero of the piece. At one point he asks the narrator whether the next chapter is about him, and when told that it is actually about Tigger, his disgruntled reaction is utterly winning. Milne’s greatest creation – and, as @elab49 pointed out, a precursor to Marvin the Paranoid Android – is Eeyore, who doesn’t have a story to himself in any of these segments but just cameos from time to time with a melancholic comment to dampen the proceedings. A particular highlight is when he is building a small wooden shelter for himself. Pleased with his handiwork he says ‘There, that should stand against anything’ before Pooh crashes through it, calling out ‘Happy Windsday Eeyore!’ Eeyore, utterly downcast, responds, after a beat, with a mournful, ‘thanks for noticing me…’ It’s sad and hilarious at the same time.

What elevates The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh from an enjoyable, beautifully animated children’s story into something that is just about a masterpiece, is the way it uses metafictional techniques, that is, moments when the story is aware of itself as a work of fiction. You see this in the way that the characters interact with the narrator (voiced beautifully by Sebastian Cabot, who was also Bagheera in The Jungle Book) and ask him to stay on one page a little longer, or when the narrator refers to a rainstorm happening ‘on page 71.’ The whole film is presented as a story within a book, and it keeps cutting back to gorgeously framed moments of the animation happening literally within the pages of the novel. Below are just a few examples of this beautiful technique.

By regularly drawing attention to the fact that this is a work of art, an unreality, through the animation techniques as described earlier and through metafiction, The Many Adventures takes on far more significant themes than what one might expect from one of their most child oriented films. It becomes about the art of storytelling, and explores the relationships between cinema and literature within this art. The interaction between the characters, the narrator and the physical words on the screen make the film simultaneously whimsical and thoughtful – no other Disney film (yet) has been quite so daring with its own form, but it is never distractingly so. It enhances the story, allowing for a greater sense of escape because of its awareness as a work of fiction. ‘Animation can explain whatever the mind of man can conceive’ – here Reitherman is explaining the mind of A.A. Milne is a way so imaginative and humourous that the author would no doubt be proud.

In an era of jazzier animation and sharper humour, The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh is a disarmingly sincere film with a deceptive intelligence, yet wide eyed innocence, that makes this one of the most winning films from Disney, even if it isn’t very Disney at all.