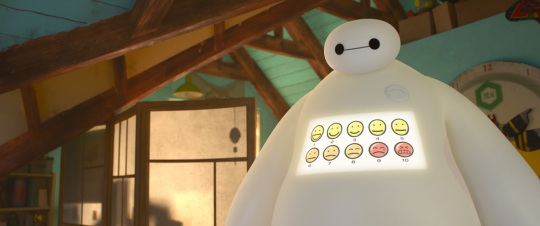

The kids I took to see Big Hero 6 were convinced that the film was actually called Baymax. It’s easy to see the confusion: all the marketing has focussed on the big marshmallow-esque robot, and the film sort of does, too. The implied team of the film’s title feature, but at the end of the day, there is one thing that everyone, children and adults alike, will remember from Disney Animation’s latest, and that is the studio’s greatest animated character of their CG era.

The friendly healthcare robot was designed by Todashi, the brother of the prodigiously talented and subtly named Hiro. When Todashi dies in a tragic accident, and a villain starts to roam the streets of San Fransokyo, Hiro, Baymax and their science-genius friends form the titular group to defeat the mysterious masked man and find out what really happened to Todashi. As plots go, it’s fairly uninspiring, the central mystery having been likened by some critics – not unfairly – to an episode of Scooby Doo. The big finale, where the whole team work together and use their tech to intelligently battle a billion tiny bots, would not feel out of place on a Saturday morning cartoon, either; it’s a fairly disposable Disney denouement.

Except for when Baymax is involved.

There is much to admire about the film aside from Iron Man’s cuddly cousin. Where many superhero films are content to let thousands of civilians die and have whole cities erased for the sake of a BIG final act – ironically making them all uninteresting and indistinguishable from one another – Big Hero 6 is a superhero film with almost zero collateral damage. The team focus their skills and technology on protection, not violence, and this emphasis is crucial and refreshingly different. The animation is impressive, too, rendering the hybrid city of San Fransokyo in vivid colours that would make Christopher Nolan tut in disapproval. The whole film is just a lot of bright fun, and goes some way to restoring a light touch to the tired and serious superhero subgenre.

It is, however, all about Baymax. You are probably already familiar with his look: white airbags; a low centre of gravity; a face like an emoji. It’s a beautifully minimalistic piece of character design, making the most of Disney’s age old animation principle of Squash and Stretch (exactly what it sounds like), while maximising one of their other twelve principles, Appeal (the idea that every character should be animated in a way that appeals to an audience), simply through its movement. It’s textbook stuff – literally, in that the principles are laid out in The Illusion of Life, as close as Disney gets to a textbook – used since Snow White but here being applied with equally cutting edge technology. From the way that he waddles along, even when in a dramatic chase, to the way the tilt of his bulbous head can evoke emotions, Baymax shows that Disney are still masters of character animation, and that no matter how new and shiny your programmes are, you still have to use them well.

Baymax is more than just an object lesson in how to animate a character, he‘s also a perfect example of how to use character to explore themes in interesting and new ways. Grief and loss are weighty topics for a kids‘ film to tackle, but also important ones; kids all have to confront death for the first time at some point in their lives, so using cinema to explore that is a great idea. The first act gives Todashi enough screen time to really make his death felt by the audience, and the rest of the film is about coping with that loss. The directors use Baymax to explore this by the literal-thinking robot seeing Hiro’s sadness as something that can be cured and so the internal process of Hiro’s grief is externalised in a deft manner, managing to be light-hearted and funny without ever detracting from the seriousness of the topic. The themes are, therefore, inextricable from the two characters at the centre of the story.

The result is a character who, in a Disney film in the early ‘00s would have been a comedy sidekick, is now the emotional heart of the film. It’s a such a simple but effective concept it’s amazing it hasn’t been done that much before (something like Robot and Frank is the closest comparison). The finale only transcends its familiarity when it focuses on the relationship between Baymax and Hiro, and creates something special. Big Hero 6 as a whole, while a lot of fun, will not go down as one of the studio’s revered classics, but Baymax will be remembered as one of their greatest creations.

I’ve been quiet on this blog of late – that’s because I’ve been privileged enough to be writing for other people! For example, a Miyazaki Blu ray boxset came out recently, and I wrote about it for two different outlets. Below are a paragraph from each of those, and a link to the full article for those who are interested. Maybe 2015 will offer more opportunities for me to keep up with Animation Confabulation…

Astonishment And Empathy – My piece for Vodzilla

Miyazaki’s most distinctive quality, his vivid and unparalleled imagination, was present from his debut feature, The Castle of Cagliostro. Starting out in 1979 with this pacy adventure of dashing thieves and crumbling castles, the then young upstart established himself as a fiercely creative mind, injecting a formulaic princess-trapped-in-a-tower plot with as much visual verve as possible. Cars don’t turn, they careen (bad drivers are a recurring theme in his films), while the final action sequence takes place inside a clocktower, a scene so thrilling that Disney would homage it only a few years later in Basil: The Great Mouse Detective. His last film, 2013’s The Wind Rises, has invention spilling equally out of the frame, even though it is ostensibly his most realistic film. Whether in the gorgeous dreams of flight that punctuate the story, or in the way the earthquake is depicted as a series of waves swelling beneath the earth, the brightness of the man’s mind remains undimmed by non-fiction. And those are the only two films in his canon that couldn’t be classified as a fantasy – the rest of his work is even more dazzlingly inventive.

The greatest director ever – a review for Front Row Reviews

Equally remarkable is the way that Miyazaki can craft such compelling stories without resorting to clearly defined villains, and often removing conflict from his narratives altogether. Howl’s Moving Castle and The Wind Rises both clearly show a revulsion to war, although it is never quite as explicit as in the films of his colleague Isao Takahata, but this desire for peace and balance goes further than pacifism on a broad political scale; Miyazaki’s peace is ingrained in the very nature of his stories. In Laputa, Nausicaa, Mononoke and Ponyo, the conflict is with nature itself, but a peaceful resolution is achievable in every single one of them, often with nature triumphing. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, My Neighbour Totoro, and Spirited Away, there is no binary conflict at all, where the story lies in simply observing the characters, with a magical element thrown in to spice things up. This clash of the magical and the mundane is precisely the appeal of Miyazaki. His are films that champion the imagination of the everyday, revealing the mysterious beauty that hides beneath tree trunks and round street corners.

The Boxtrolls tells the story of a young boy who grows up with the titular cardboard-bound monsters, and how he has to save them from a band of troll-catchers who have convinced the town that the harmless creatures are, in fact, evil. But it’s also about a city obsessed with cheese, a class system based on hats and a girl who is obsessed with death and violence. It’s gross, silly, sharply satirical and is actually for children. It must be a Laika film.

Laika, the animation studio behind under-appreciated marvels Coraline and ParaNorman, are exceptionally hard workers. Animation is a time consuming process that requires a near miraculous attention to detail, but stop motion animation, the process of taking 24 photos of precisely positioned models for every second of film, is a doubly difficult discipline. Every minute of footage you see contains 1,440 photos, so The Boxtrolls, their latest film which runs at 100 minutes, is 144,000 photos long, each one moved ever so slightly to create the illusion of life. Any stop motion film even existing is reason, therefore, for celebration. Laika go the extra mile by making each of their films immensely imaginative and distinctively theirs, making each new release something to be greatly anticipated. Yet there is a sense with The Boxtrolls that the animators are fed up of going unnoticed – some early promotional material focussed on how much work they put in, while a hilarious mid-credits sting shows the animators at work. They want people to see what they do, that they are hard workers.

The animators have nothing to fear; as long as there are critics with an eye for good animation out there, the skill and ingenuity of The Boxtrolls will be championed in every column inch around the country. Once again, Laika impresses on two levels with their standard of animation. Firstly, on a technical level, they achieve a fluidity of motion that leaves behind the juddery days of something like The Nightmare Before Christmas. Characters slide, fly and run around the screen and it is impossible to see the process behind it – perhaps another reason for the animators wanting to make themselves noticed. The trolls themselves are the best thing about the film, all green and grey and warty but instantly loveable thanks to superb character design and the neat trick of naming them after what their box previously contained. Without speaking any English, the trolls become immediately recognisable and sort of iconic thanks to the skill of the people making them move.

Yet The Boxtrolls is also remarkable for the fact that the film has a distinctive, grotesque aesthetic that sets it apart from the rest of American animation that can, occasionally, veer towards the visually homogeneous. If the big new studios of the US are schoolkids, Pixar is the handsome, loved-by-all prom king, Dreamworks is the class clown who tries a little too hard to be as loved as the prom king, Blue Sky is the tag-along in the jock crowd and Laika is the weird kid in the corner whose notebook is covered with macabre doodles, who wears black even in summer and who won’t even go to prom because he’d rather stay home and watch horror films. The Boxtrolls is an ugly, different film, but brilliantly so. Nothing is quite the shape it should be, with roads twisting and turning round architecturally dubious houses populated by bulbous and bony people. Laika’s films have more in common with Jan Svankmajer and Jiri Trnka than any of its American contemporaries. They are gradually carving out their own gnarled niche in the market, and it’s constantly refreshing to see.

Another apparent influence is Charles Dickens, both in the visuals but also in the astute social satire. The great Victorian novelist, who was obviously writing before cinema existed, had a flair for using the imagery of architecture and people to reflect something of their personality. Coketown, a fictional Manchester-alike city in Hard Times, has “chimneys that were built in an immense variety of stunted and crooked shapes, as though every house put out a sign of the kind of people who might be expected to be born in it,” a description that could equally apply to the thoroughly Dickensian Cheesebridge of The Boxtrolls. Its people, too, are straight out of one of his satires, with inhuman shapes used as shorthand for class status or narrative role, and names such as Archibald Snatcher and Lord Portley-Rind are not a far cry from Josiah Bounderby. All of this serves a purpose for the film, in that (as with ParaNorman), the writers and directors are interested in making a point as well as telling a story. This is a society where the elites are demarcated by the colour of their hat and the quality of their cheese, and where the city’s rulers will spend money on a giant wheel of brie instead of a children’s hospital. It’s exaggerated and absurd, but surprisingly pointed in its absurdity. Dickens would certainly approve.

What The Boxtrolls has also inherited from the writer of Hard Times, however, is a broadness that comes at the cost of pace and purpose. Just as Dickens had multiple targets that he skewered over hundreds of pages, so too do directors Graham Annable and Anthony Stacchi attempt to cover a lot of issues over a much shorter running time. Class systems, self-actualisation, persecution of difference, good and evil, fatherhood and learning to stand up for yourself are all themes that are covered by the plot, and some of them land with more impact than others. A subplot involving the villain – voiced by Ben Kingsley in a manner so over the top and hammy that it ultimately lessens his impact – and his allergy to cheese but his insistence on eating it, just doesn’t work and slows the film down to a halt. Although it does culminate in a surprising and hilarious climax, it also drags out the finale for a scene too long. By trying to cram in so many ideas, The Boxtrolls misses out on the emotional power of ParaNorman, which conveyed its message far more efficiently.

Ultimately while the pacing and lack of focus of The Boxtrolls stop it just short of greatness, it is, still, a Laika film and it contains all the hallmarks of what makes that such a special thing. The animation is incredible, the humour hits the mark and it is full of ideas and invention. Not everything works, but this is still an impressive, ambitious and unique film and, as such, it deserves to be cherished.

The first How To Train Your Dragon film ended on a surprising note for a big studio animation in that the main character lost one of his legs. Contrary to just about every other animation out there, the action sequences in the spectacular finale had actual consequences. It’s a bold move, and was one of the many elements that made it stand head and shoulders above everything else Dreamworks animation – and most other CG studios – has released. There is a scene in the middle of that film’s stunning sequel that takes such consequences to a new level that is, again, completely surprising for studio animations of the CG era. This is just one aspect of the first film that has been carried over into the second film, not in a lazy, same-but-bigger approach, but in a way that it keeps everything that made the first so good, all while telling a different story. In that sense, it’s up there with Toy Story 2 & 3 as one of the best animated sequels ever.

Moving five years on from the events of the first film – itself a move that feels remarkably fresh – the protagonists of the first have grown up and Berk is now well established as a dragon riding village. Astrid and Hiccup are still a couple and nothing threatens that throughout the film, they just work consistently well together. Hiccup and his father, Stoick, are no longer just an awkward father and son but friends who have disagreements; their relationship has moved on so that the conflicts are different – now it’s about how to lead and who should lead. In short, there is real progress from the first film. Where the Shrek films repeated the same story four times in a row, what makes the world of Dragons so absorbing is that even though it is clearly fantastical, it’s a world where people grow up, where relationships develop and people are put in actual, real danger. In that sense, it’s more mature than most live action blockbusters where characters are stuck in a stasis of immortal, bland superheroics.

Thrown into the mix of these developing relationships to shake things up is a mysterious dragon rider wearing a spiked mask and formidable armour, whose identity was sadly given away in the trailer. If you don’t want to read about this early plot development and missed the trailers, skip to the next paragraph. She is Valka, the original dragon rider and, of course, Hiccup’s mother. The big family reunion is marked not by histrionics but by tender moments, for instance a wonderfully unprofessional duet is how a husband and wife rediscover their love for each other. This family unit is one of two relationships that form the core to a film that is regularly surprising in its emotional impact. Considering, again, where other Dreamworks films may have taken this subplot, the maturity of Dragons 2 is evident. There is no forced conflict, no big fall out to be followed by an equally trite resolution, but curiosity and happiness instead. It’s romantic in a restrained way, both heartfelt and believable.

The other key relationship is, of course, Hiccup and Toothless. Easily the highlight of the first film, here their bond is expanded and challenged in fascinating, sometimes heartbreaking ways. Toothless, now rendered with astonishing detail, is one of the greatest animated characters ever, every expression, every movement conveying a wealth of character without ever fully anthropomorphising him – he remains a dragon throughout. He’s a fully rounded creature, with a personality and tics that utterly sells him as real and tangible. It’s therefore immensely distressing when his relationship with Hiccup is tested to its extremes in the third act. This is a double act you are rooting for from the first scene they are in together, thanks in part to the work of the first film but also to the work done by the animators and Jay Baruchel as Hiccup to convince us of their bond as best friends.

It’s not just the animation on Toothless that is impressive, but the whole world is created with the kind of detail and flair that causes jaws to involuntarily drop and animation geeks to drool uncontrollably. Technologically there have been huge leaps, with Dreamworks pioneering new lighting and movement software that shows in the texture of a dragon’s skin or in the thickness of a fur coat. Yet technologically impressive animation does not make it necessarily visually interesting. Dean De Blois’ direction, however, assures this film’s place as one of the best looking CG animations of all time. As Hiccup narrates, ‘with Vikings on the backs of dragons, the world just got a whole lot bigger,’ and both the world and dragons are, indeed, a whole lot bigger; exploring this world is where Dragons 2 really takes off, as Hiccup discovers more about dragons, sees more types and tries to map the world. Some of the images that De Blois and his team creates are utterly breathtaking, from a montage of feeding and soaring on thermals, to a widescreen shot of solo flying that looks astonishing in IMAX.

It’s as though the creators of How to Train Your Dragon 2 set out to show us things we’ve never seen in the cinema before, such is the ambition and scale of some of the shots. Take, for instance, the introduction of Valka. Hiccup is having a small tantrum while flying high on the back of Toothless. Unknown to him in the background, a masked figure pierces the tops of the clouds and drifts by, standing proud and upright and seemingly floating, unassisted, through the pearlescent sky. It’s a powerful, strange image that’s almost scary it’s so compelling. When Valka introduces herself later on in a cave full of dragons, it happens to the burning light of a dozen dragons using their mouths as torches and once again the film makes you gasp at the beauty and invention of the image. Accompanied by John Powell’s score that sets hearts racing and lifts spirits, Dragons 2 is full of unforgettable moments like this that inspire awe and wonder, which is exactly what animation, and cinema in general, should be doing.

Michel Gondry, even at his worst, is a visually inventive film maker who can create memorable images from something as middle of the road as The Green Hornet. Animation plays a big part in The Science of Sleep and Mood Indigo, so for him to do a fully animated film was an enticing prospect. His choice of subject, however, is a strange one. Is The Man Who Is Tall Happy? is a serie

Michel Gondry, even at his worst, is a visually inventive film maker who can create memorable images from something as middle of the road as The Green Hornet. Animation plays a big part in The Science of Sleep and Mood Indigo, so for him to do a fully animated film was an enticing prospect. His choice of subject, however, is a strange one. Is The Man Who Is Tall Happy? is a serie

s of interviews with Noam Chomsky by the distinctive French director, animated, apparently, using felt pens and acetate.

Chomsky is a popular liberal thinker and linguist whose work, for some reason, I hadn’t really encountered before, so I was approaching this as a Gondry and animation fan, rather than a Chomsky acolyte. Thankfully, the polymath is an engaging, worryingly intelligent subject, here discussing the development of language in childhood and how we come to understand signs and signifiers. More charming than the interviewee, however, is the interviewer; Gondry is marvellously self-deprecating, openly confessing when he doesn’t understand what is happening, or when he got tired of animating a particularly long sequence. His questions are thoughtful, his responses funny and he makes an excellent foil to the rather serious Chomsky. Together the two of them make an electric double act as ideas are thrown around and the audience are left feeling a little bit stupid.

At the beginning of the film, Gondry explains why he is animating it. All film – documentary included – is a form of manipulation where the director or editor controls how the audience receives the information. Gondry’s conclusion, therefore, is that animation is a permanent reminder that you are watching artifice, that the version of Chomsky we are seeing is one that is undoubtedly being presented to us via someone else (something that is reinforced by the repeated whirring of an old camera). Gondry then releases the viewer to engage with all the ideas without restraint. The animation is lo-fi but captures the energy of the discussion perfectly, often repeating movements and images to suggest the circularity of the language, and using crude drawings of the two talkers to depict the mood of the conversation; it’s not always gentle discourse. What really works is that the often difficult intellectual ideas to get your head around are given perfect clarity by Gondry’s perfectly judged visualisations of these big themes. The director’s humour seeps into his drawings, too, making this a surprisingly light and accessible film that can be enjoyed even by those who dread discussions about knowledge endowment and its expression through language.

Is The Man Who Is Tall Happy is playing at Edinburgh International Film Festival on the 20th and 27th June

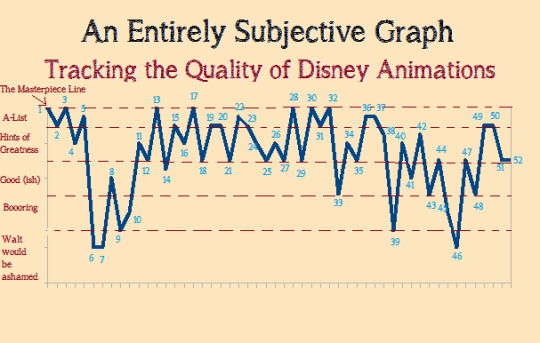

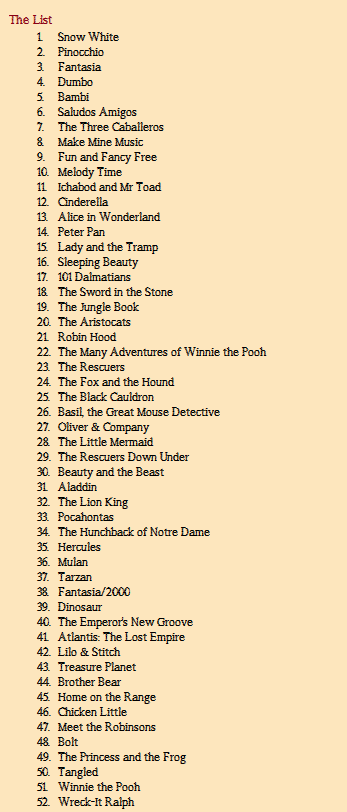

I love lists. I know a lot of film fans think they are reductive, and they are right. However, they are also immensely fun to do. So here is a list of my favourite 20 Disney films, which is liable to change any day of the week but looking back over the project I reckon this is a rough estimate of my favourites. I started out with 10 but then felt bad for 10 more films I didn’t mention. Then after that I’ve included some more lists (the most difficult list was actually the last one!). I told you I love lists. I’ve not included Frozen, but I don’t know why not.

Please comment below with your versions of whichever lists interest you the most.

My 20 Favourite Disney Films

20. The Fox and the Hound

19. Aladdin

18. Tangled

17. The Rescuers

16. Lady and the Tramp

15. The Aristocats

14. The Princess and the Frog

13. Pinocchio

12. The Jungle Book

11. Tarzan

10. Bambi

09. The ManyAdventures of Winnie The Pooh

08. Mulan

07. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

06. The Little Mermaid

05. Fantasia

04. Beauty and the Beast

03. 101 Dalmatians

02. Alice In Wonderland

01. The Lion King

05. Fun and Fancy Free

04. Dinosaur

03. The Three Caballeros

02. Chicken Little

01. Saludos Amigos

The 10 Best Disney Songs

10. Zero to Hero (Hercules)

09. Colours of the Wind (Pocahontas)

08. Down in New Orleans (The Princess and the Frog)

07. Under The Sea (The Little Mermaid)

06. Make A Man Out of You (Mulan)

05. Everybody Wants to be a Cat (The Aristocats)

04. Why Should I Worry (Oliver and Company)

03. Strangers Like Me (Tarzan)

02. I Wanna Be Like You (The Jungle Book)

01. The Circle of Life (The Lion King)

The Five Best Disney Villains

04. Maleficent (Sleeping Beauty)

03. Scar (The Lion King)

02. Count Frollo (The Hunchback of Notre Dame)

01. Dr. Facilier (Princess and the Frog)

The Five Best Supporting Characters

05. Mushu (Mulan)

04. The Mad Hatter (Alice in Wonderland)

03. Lumiere and Cogsworth (Beauty and the Beast)

02. Grumpy (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs)

01. Kronk (The Emperor’s New Groove)

The Five Disney Films That Might Be Underappreciated For Whatever Reason*

05. Basil, The Great Mouse Detective

04. Meet the Robinsons

03. The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh

02. The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad

01. Alice in Wonderland

*possibly the most subjective category, I get it

The Five Weirdest, Strangest, Downright Bizarre Disneys

The Five Weirdest, Strangest, Downright Bizarre Disneys

05. Pinocchio

04. The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad

03. Alice In Wonderland

02. Fun and Fancy Free

01. The Black Cauldron

The Five Disney Films With The Best Soundtracks

06. The Lion King

05. Tarzan

04. The Jungle Book

03. The Princess and the Frog

02. Beauty and the Beast

01. Fantasia (cheating, I know)

Five Heroes of Disney

05. Phil Harris (Voice Artist, The Aristocats, The Jungle Book, Robin Hood)

04. Sterling Holloway (Voice Artist The Rescuers, The Rescuers Down Under, The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh)

03. Alan Menken (Composer Most of the 90s films)

02. Wolfgang Reitherman (animator, director all the films from 101 Dalmatians to The Rescuers)

01. Walt Disney (Producer, insigator, entertainer)

The Five Films I’m Most Nostalgic About

05. Aladdin

04. The Hunchback of Notre Dame

03. Mulan

02. Beauty and the Beast

01. The Lion King

The 10 Disney Films With The Best Animation

10. The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh

10. The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh

09. Lady and the Tramp

08. Pinocchio

07. Bambi

06. Alice in Wonderland

05. 101 Dalmatians

04. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

04. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

03. The Lion King

02. Sleeping Beauty

01. Fantasia

This is just a quick note to say thank you to everyone who has helped out over the course of the #Disney52 Project. It ended up being quite a big undertaking for me in the end and it meant that it couldn’t have been done without quite a few people, so here are some thanks.

Firstly, thank you if you read one or any of the articles I posted as part of the project. I wrote it for fun but it’s immensely gratifying when someone actually reads the thing.

To all the people that lent me DVDs over the course of the project, thank you.: Rachael; Jennifer; Alice; Naomi (I promise I’ll give you back your copy of the Little Mermaid at some point).

To some tireless promoters of the blog: anyone that has linked to any article; Noel; Cecilia; Mike; with a bike; Paul (who I slagged off in one of my articles); Elab; Sam, who doubled my blog’s views in one day by posting my Peter Pan article to Reddit.

To those that have been regular commenters, thank you for joining in the conversation: The Animation Commendation; Noel (again); Tim;; smallerdemon; Edwin; Karel; Simeon – sorry to anyone I’ve forgotten, these were the ones that stuck in my head.

To anyone that hasn’t laughed at me for watching kids’ films, thanks.

As I’ve previously mentioned, 2013 was a diresome year for fans of animation. Ideas were low, talent was apparently lower. Stinkers abounded and even the more dependable studios like Dreamworks and Pixar made either dreadful (in the case of Turbo) or underwhelming films (The Croods, Monsters University). The less said about Planes, the better. Thankfully, however, 2014 looks set to remedy the creative malaise experienced in the year we shall no longer talk about, so here are six animated films you should be getting excited about in the next twelve months.

The Wind Rises

Hayao Miyazaki’s latest film should be the main draw of the year based on the ‘directed by’ credit alone, but the fact that this has already been a huge (but controversial) hit in Japan should whet your appetite further. It’s attracted criticism from Japan’s political right wing for being too critical of war and from Japan’s political left wing for lionising the man who made planes that killed lots of people. Miyazaki has claimed he just wanted to tell a good story about a great engineer, so I think I’ll stick with his version of events. The trailer promises beautiful animation – as ever – and a chance for the legendary director to indulge in his love of flight. Expect one of his least fantastical films yet, but still filled with the sense of wonder that characterises all of his stories.

The Tale Of Princess Kaguya

Isao Takahata could be seen as the Ghibli outsider, despite being a collaborative partner with Miyazaki since the beginning of the studio. Although he has made some unforgettable films with the studio, he isn’t a well known name like Miyazaki and few people have seen Only Yesterday. His films tend to be far more low-key and reality based (apart from the bizarre Pom Poko), but that dynamic has shifted as this film – based on an ancient Japanese legend – is about a tiny girl who is discovered inside a bamboo shoot. Promising to be moving and enchanting, it’s Takahata’s first film in fourteen years. Welcome back.

How To Train Your Dragon 2

Almost any film this year could disappoint me and I wouldn’t mind, but my one hope for the year is that this doesn’t suck. I love the first one so much: the score; the animation; the ‘test drive’ scene. The early trailers for this suggest that it will be more of the same, so I’m cautiously excited. Let’s just hope it’s more Toy Story 2 than The Lion King 2 (which is actually ok, as Disney sequels go, but still: whyyyyyy).

The Boxtrolls

Laika’s previous films Paranorman and Coraline were both visual marvels, stop-motion animations that defy the jerkiness often associated with the medium. The team have mastered the art of taking thousands of photos of tiny figurines and turning them into compelling, moving stories. The Boxtrolls is about a boy who has been raised by the titular monsters and has to save them when an exterminator threatens to wipe them out. Expect it to be a little bit macabre, beautifully animated and pushing the envelope for children’s entertainment.

Big Hero 6

Disney are on something of a roll at the moment so my apprehensions about this feature – sounds like the tone will be similar to The Incredibles, and it always irks me when Disney try to be Pixar; not sure I always like concept over character when done by Disney – are outweighed by general positive feelings towards the studio and curiosity as to what the apparently photo-real animation will end up looking like on the big screen. There hasn’t been much information released about this film yet, but I remember being worried that Frozen was going to suck and so I’ve decided to just wait and see with the House of Mouse. They’ve surprised me several times before, so I’m willing for that to happen again.

The Lego Movie

Phil Lord and Chris Miller made the magnificent Cloudy With A Chance of Meatballs and the hilarious yet deceptively astute comedy 21 Jump Street, so with a 100% record so far I’ll give them the benefit of the doubt on this one, which could be dismissed cynically as a marketing ploy for the toymaking giants. The trailer already makes me laugh a lot, plus the song ‘Everything Is Awesome’ is, well, awesome. If anything, by casting Will Arnett as the caped crusader, The Lego Movie looks set to have the best onscreen Batman since Adam West.

2014 will also have a sequel to Planes, named Planes: Fire and Rescue. I shall endeavour to remain open minded…

It’s always difficult to say at the end of a year what will be remembered and what will be forgotten, but looking back over 2013 I suspect that very few of the blockbusters of this year will be remembered. What might last, however, are the smaller films championed by a few that will only gain fans over time, or the odder, more difficult films that maybe require multiple viewings to really appreciate.

Man of Steel, one of the worst superhero films ever, topped off a list of disappointing blockbusters like Star Trek Into Darkness and Thor: The Dark World; films that maybe had an impressive sequence or two but were just plain forgettable. They brought in the punters to the box office, but it’s unlikely that anyone will discuss Into Darkness with any affection 5 years from now, or even discuss it at all. Iron Man 3, Pacific Rim and Elysium were all enjoyable in their own ways, and Gravity was technically astonishing and provided the most spectacular scene of the year, but the general consensus is that this last year was disappointing for fans of big franchises and bigger budgets. Perhaps to blame is the increasing homogeneisation of the blockbuster scene as part of the countdown to the Hollywood apocalypse that will be 2015; anything churned out by the formula adhering studio system felt like it was the product of a calculating brain trust as opposed to a team of passionate creatives. On the whole, Hollywood’s output in 2013 was just dull, and the result is that many big name film publications were quick to dismiss the year as a bad one.

Anyone who dismisses an entire year, however, probably isn’t watching enough films. Looking back, 2013 was filled with some wonderful cinema; films that cared more about telling stories than blowing stuff up. Here in Britain, Clio Barnard‘s phenomenal The Selfish Giant impressed just about anyone that saw it, and one suspects that its reputation and respect will only grow with time. Philomena, Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa, A Field In England, For Those In Peril and, ahem, Les Miserables among others all kept the British end up as well, while the American indie scene was well represented by The Way, Way Back, All Is Lost, The Kings of Summer and Ain’t Them Bodies Saints – all of which were directed by fairly young, new names. As ever, cinema from around the world also produced some exciting, fascinating films with Saudi Arabia’s first ever film Wadjda the best of a list that included Blancanieves, Caesar Must Die, In The House, and a number of films that were only available at festivals such as Attila Marcel, Faro and Historic Centre.

The biggest disappointment of the year, however, was animation in general. From Up on Poppy Hill and Wolf Children, two of my favourites from last year, got limited cinematic releases, while Makoto Shinkai’s astonishing The Garden of Words got its festival debut here, but leave Japan behind and the picture is bleak. Disney’s Frozen was the only American animation that left wholly smelling of roses and Cloudy With A Chance of Meatballs 2 managed to be one of the funniest films of the year, but The Croods, Monsters University and Epic were all a little bit disappointing. Then further down the quality scale, Turbo, Despicable Me 2 and Planes were all truly dreadful and I’ve heard bad things about Justin and the Knights of Valour, Free Birds and Walking With Dinosaurs, all of which I sadly missed. It’s been a bad, bad year for animation, but perhaps 2013 will go down in animation history as the year that Sir Billi was released, an execrable independent animation from up here in Scotland. A full review is coming for that film but no words can properly describe just how awful it is. Still, at least 2014 looks to set the animated record straight.

Anyway, below are my arbitrary awards and a list of my favourite 20 films of the year. You’ll notice the general paucity of animation there, and I should point out that Michel Gondry’s brilliant The We and the I was something I was privileged to see at Glasgow Film Festival but I don’t think has had a UK release yet. And yes, I really did like Les Miserables that much and I’m only a little bit embarrassed to admit it. If you were wondering about the title of this article, that’s my favourite quote of the year, taken from the incredible Frances Ha.

My Favourite 20 Films of the Year

1. Wadjda (Haifaa Al Mansour)

2. Cloud Atlas (Tykwer & Wachowskis)

3. The Selfish Giant (Clio Barnard)

4. The We and the I (Michel Gondry)

5. Les Miserables (Tom Hooper)

6. Philomena (Stephen Frears)

7. The Way, Way Back (Rash, Faxon)

8. Caesar Must Die (Taviani Brothers)

9. Blancanieves (Pablo Berger)

10. Ain’t Them Bodies Saints? (David Lowery)

11. Frances Ha (Noah Baumbach)

12. A Field in England (Ben Wheatley)

13. Frozen (Buck & Lee)

14. All Is Lost (J.C. Chandor)

15. The World’s End (Edgar Wright)

16. Robot and Frank (Jake Schreier)

17. Leviathan (Castaing-Taylor, Paravel)

18. Lincoln (Steven Spielberg)

19. Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley)

20. Mud (Jeff Nichols)

I haven’t included From Up on Poppy Hill or Wolf Children as I harped on about them enough last year. Also worthy of mention is the brilliant Safety Not Guaranteed which barely got released right at the tail end of 2012.

Worst Film: Sir Billi

Film I Hated Most: Pain and Gain

Best Performance: Waad Mohammed, Wadjda

Best Visuals: Ain’t Them Bodies Saints (honourable mentions: A Field in England, The Selfish Giant)

Best One-Person-Against-the-Odds Film: All Is Lost

Most Sexist Film: Oz, The Great and Powerful

Best Re-Release: The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser

Best Score: Cloud Atlas

Biggest Disappointment: To The Wonder

Best Film I Didn’t Get: A Field In England

Worst Film I Didn’t Get: Upstream Colour

Best Comedy Cockerel: Blancanieves

Films I Still Haven’t Seen But Maybe Intend To: The Act of Killing, The Place Beyond the Pines, Before Midnight, Beyond The Hills, Something In The Air (Apres Mai), Computer Chess, Only God Forgives, Ernest Et Celestine

Most Bafflingly Adored By Critics: Django Unchained

Film With The Best Extras But Was Otherwise Rubbish: Sunshine on Leith

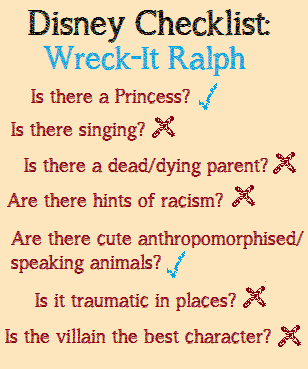

What do The Purge, In Time and Wreck-It Ralph all have in common? They are all films that squander brilliant concepts in favour of something far more generic. What makes Wreck-It Ralph better and yet more frustrating than those two forgettable films is that the first act really properly explores its central concept in a way that it utterly fails to do in acts two and three. It’s a film built on a fantastic, Toy Story-esque premise – what do computer game characters do when no one is playing – that is subsequently abandoned in favour of something far less interesting about a friendship between two misfits and how they both earn respect. The genius idea that was crying out for a bonkers, cross-game finale instead gets stuck in a swamp of literal and figurative sugar. So, let’s explore this problem further:

What do The Purge, In Time and Wreck-It Ralph all have in common? They are all films that squander brilliant concepts in favour of something far more generic. What makes Wreck-It Ralph better and yet more frustrating than those two forgettable films is that the first act really properly explores its central concept in a way that it utterly fails to do in acts two and three. It’s a film built on a fantastic, Toy Story-esque premise – what do computer game characters do when no one is playing – that is subsequently abandoned in favour of something far less interesting about a friendship between two misfits and how they both earn respect. The genius idea that was crying out for a bonkers, cross-game finale instead gets stuck in a swamp of literal and figurative sugar. So, let’s explore this problem further:

Act 1. The Anti-Hero is introduced as Wreck-It Ralph, who works in the arcade game Fix It Felix Jr, where every day he wrecks the building only for it to be fixed by the game’s hero, Felix. As the game approaches its thirtieth anniversary, Ralph begins to resent his role as the bad guy and seeks a little bit of appreciation for his work as a human wrecking ball. He shares these feelings with a group called bad-anon, and here is where the film reveals its trump card: a cast of recognisable computer game characters from decades of arcade and console games. Bowser, Dr Robotnic and Clyde (from Pacman) all attend this self-help group where they build up each others’ self esteem. It’s a witty idea made funnier by the presence of such familiar villainous faces.

The rest of Act 1 builds on this idea, exploring a number of different game worlds, often cutting to show what they look like on 8-bit Arcade screens as opposed to in state of the art CG. Game Central Station, the hub of all the machines, is populated by a vast array of characters to please an audience of die hard gaming fans. Sonic, Frogger and the exclamation mark from Metal Gear Solid all cameo, but what makes the first act so great is that these cameos don’t detract from original, intelligent world-building. The biggest idea of the film is not to cast Pacman in it, but is in the way that different gaming characters interact with one another; it’s the idea of a life behind the screens where people worry, party, drink and commute just like humans do. The jealousy and admiration for the newer, flashier games, and the fear of your arcade getting closed down both feel like real world concerns, which is what makes this world so engaging. Ralph’s infiltration of Starship Troopers-meets-COD game Hero’s Duty shows what can happen when different games cross over. It’s a premise ripe with the potential for excitement and big laughs. And then…

Act 2. Ralph crash-lands a ship from Hero’s Duty in the everything-is-made-of-candy racing game Sugar Rush. He accidentally brings an apparently asexually reproducing bug with him – more on that later – but is more concerned with his medal, his way of proving that he can be a hero, not just a bad guy. He meets Vanellope Von Schweetz, a ‘glitch’ in Sugar Rush, who uses his medal to get in the big race. The two then bond as she learns to race and he continues his existential crisis. Here’s where the main bulk of the story happens, as he confronts the villainous King Candy and helps Vanellope with her car before a big conclusion where she has to race to reset the game, but a horde of violent, viral insects are rampaging through the U-rated universe of Sugar Rush.

There’s a lot to like about this section, not least of which is a dramatic conclusion with a surprisingly emotional slo-mo act of sacrifice to save the day. The problem is that the film then doesn’t leave the world of Sugar Rush, thus ignoring the genius bit of world-building that was established in Act 1. The candy kingdom is nicely realised and allows for a couple of great puns worthy of Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, but this film shouldn’t be about Sugar Rush; the racing game should be just one part of a much bigger picture with Game Central Station or Fix It Felix as the central focus. As it is, that Cloudy comparison wasn’t arbitrary, with the second act feeling like an early sequel to that brilliant film, whereas the first act was far more in the vein of The Incredibles or Toy Story. The film spends far too long in this game, outstaying its welcome when the audience are itching to leave behind its candyfloss colours. It’s almost as if two entirely different studios made two different films then forced them together, with the designers behind Sugar Rush apparently more powerful in the editing sweet.

Act 3. So what now, for the future of Disney? The tonal disparity in Wreck-It Ralph is representative of how the studio in the 21st century, bar one or two marvellous exceptions, was struggling to find its voice in the world of modern animation. If the first sugar-free half hour of Wreck-It Ralph was Disney doing their best Pixar, then the second half is Disney looking dangerously like Dreamworks, saccharine in every way and following a fairly rote buddy comedy formula. Ralph shows that the studio is capable of great ideas, of stunning animation, memorable characters and good films. Yet it also shows how unsure of themselves they can sometimes be, a problem which has plagued them since Hercules.

Clearly, the studio are on the up: Wreck-It Ralph is a good film, and it comes after The Princess and the Frog and Tangled, two superb, old fashioned animations quite different to Ralph‘s post-modern sensibilities. And in Frozen, Disney have managed their best attempt yet at balancing the old and new, mixing age old stories with newer ideas and techniques. Ralph goes too far in the direction of the latter and ends up losing its identity along the way. The best step forward that Disney can take now is just that: a step forward, but provided that they do it with an acknowledgement and respect for the generations of Disney films that have gone before them. With such a long lasting legacy of truly excellent film making, Disney are the animation studio with the greatest opportunity to move into the future of animation with a strong foundation in the past. I think Walt himself would look back on the 52 films I’ve covered this year with a pride at the way that his studio has explained whatever the mind could conceive.