Winnie the Pooh seems to be forgotten about in the UK. For some time now, Disney have been putting the number of the classic on the side of DVDs and Blu-Rays. These numbers correspond with when they were released in cinemas and I’ve been following that order for this very project, right up until No.50, Tangled. Number 51, according to the sides of boxes in the UK, however, is Wreck-It Ralph. A confusing blip, as most other sources list Winnie as 51 and Ralph as 52, hence the idea of the project to watch 52 in a year, one a week (though I hardly stuck to that by the end). Yet Winnie the Pooh was undoubtedly made by Walt Disney animation studios and it DID have a theatrical release over here. So why the decision to leave it out of the canon? It’s perhaps a triviality but for an obsessive like myself it’s disconcerting. Will all future Disneys in the UK be one number behind? Perhaps Disney were embarrassed by Pooh, although that hardly seems likely as the film is a charming, child friendly ramble through the Hundred Acre Wood.

Winnie the Pooh seems to be forgotten about in the UK. For some time now, Disney have been putting the number of the classic on the side of DVDs and Blu-Rays. These numbers correspond with when they were released in cinemas and I’ve been following that order for this very project, right up until No.50, Tangled. Number 51, according to the sides of boxes in the UK, however, is Wreck-It Ralph. A confusing blip, as most other sources list Winnie as 51 and Ralph as 52, hence the idea of the project to watch 52 in a year, one a week (though I hardly stuck to that by the end). Yet Winnie the Pooh was undoubtedly made by Walt Disney animation studios and it DID have a theatrical release over here. So why the decision to leave it out of the canon? It’s perhaps a triviality but for an obsessive like myself it’s disconcerting. Will all future Disneys in the UK be one number behind? Perhaps Disney were embarrassed by Pooh, although that hardly seems likely as the film is a charming, child friendly ramble through the Hundred Acre Wood.

Admittedly, the two Winnie the Pooh films are a bit of an oddity in the canon, stylistically and tonally incongruous with the the other fifty. A.A. Milne’s unique brand of whimsy does not translate to gripping adventures or heartfelt fairy tales, instead creating films where the sum total of incident is a stuffed donkey losing its tail and some other toys getting trapped down a hole while they try and catch an imaginary creature. Yet this resolutely gentle style of storytelling means that the charm of the Pooh films is quite unique to these two adaptations. They’re funny without forcing it, quirky without trying and beautifully, inventively animated.

The 2011 edition doesn’t add much to Wolfgang Reitherman’s superior 1977 film The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, but it reuses the meta stylings of that children’s masterpiece often to great effect. By borrowing from brilliance this, too, hints at such invention and wit. Pooh once more interacts with the narrator (here John Cleese on fine form) and occasionally stumbles out of the illustrated sections of his book, and the writing is again affected by the events of the narrative. Words are dragged or blown or fall into the story, and the characters have even more fun with them this time. At one point, they even become a crucial plot point to help the stranded heroes. Such playfulness is always a joy to watch, and it used brilliantly in this second Pooh film.

The animation is once again unshowily beautiful, the backgrounds in particular looking a lot like Shepard’s line drawings. The colours seem to be a bit brighter this time, and the character animation is bolder and clearer than in the ’77 film, but this still looks as though it were made in a different era. It’s as far a cry from the lush lighting and immaculately detailed CG of Tangled as you can imagine from Disney, once again showing that this film feels out of place at Disney. This truly seems to be the last hand drawn film from the studio, a quietly brilliant tribute to the beauty of the medium, showcasing its capacity for invention and atmosphere even as it dies to the onward march of pixellated progress.

The only thing that feels modern about Winnie the Pooh is that the voice cast is noticeably different to the older, familiar voices of The Many Adventures. Put quite bluntly, they are just not as good, voice acting veteran Jim Cummings no match as Pooh compared to the inimitable Sterling Holloway. Bud Luckey’s attempt at Eeyore is disastrous, and the sense of the cast as a whole is that they don’t quite gel in the same way. The less said about Zooey Deschanel’s songs the better.

Winnie the Pooh feels like a small, independent production and a far cry from the studio that made hyper-slick films like Tangled and Wreck-It Ralph. It’s a low key, rusty film that moves at a different pace to everything else that Disney makes. As such, it’s sure to gain a devoted audience of young fans (and a few older ones, too), but it perhaps explains why Disney were not so keen to acknowledge it as part of their canon of classics. It’s a shame, however, that this is excluded when Saludos Amigos isn’t, as this is a happy, charming film full of gentle delights.

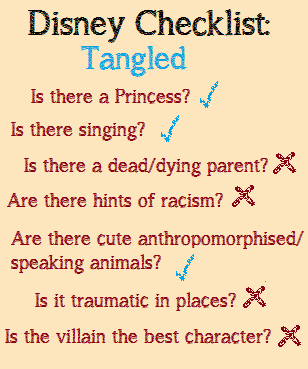

One of the joys of having done the Disney 52 project is seeing how the studio has changed throughout the decades but has remained essentially a group dedicated to entertaining people, children and adults alike, and enchanting them with magical, wondrous tales. Each generation has had a new clutch of Disney films to enjoy and nostalgia plays a huge role in the fact that almost every Disney film has someone who claims it is their favourite. The people leaping to the defense of Robin Hood, for instance, would admit to nostalgia playing a huge part in why they like it so much. The Lion King will probably remain my favourite even having seen all 52 of them because of the personal attachment I have to it. What’s nice about seeing Tangled is that you get the impression that Disney are still doing this for new generations of viewers. Tangled, despite using bleeding edge technology, is full of the charm and heart that runs through the best films the studio have made, ensuring that people in future will be citing it as their favourite Disney because they saw it at a time and place that will always be special for them.

One of the joys of having done the Disney 52 project is seeing how the studio has changed throughout the decades but has remained essentially a group dedicated to entertaining people, children and adults alike, and enchanting them with magical, wondrous tales. Each generation has had a new clutch of Disney films to enjoy and nostalgia plays a huge role in the fact that almost every Disney film has someone who claims it is their favourite. The people leaping to the defense of Robin Hood, for instance, would admit to nostalgia playing a huge part in why they like it so much. The Lion King will probably remain my favourite even having seen all 52 of them because of the personal attachment I have to it. What’s nice about seeing Tangled is that you get the impression that Disney are still doing this for new generations of viewers. Tangled, despite using bleeding edge technology, is full of the charm and heart that runs through the best films the studio have made, ensuring that people in future will be citing it as their favourite Disney because they saw it at a time and place that will always be special for them.

Not any old film can earn this accolade, however. It’s unlikely that people will still be talking about Bolt, Atlantis or Saludos Amigos in 30 years time because they aren’t especially Disney. There’s an elusive quality to some films that just makes them undeniably Disney, where you know they couldn’t come from any other studio. This doesn’t mean they tick all the boxes in my arbitrary checklist; it’s something more ephemeral than that. If you think about it, the Disney films of the 60s and 70s don’t really fit the mould of the Golden Age films, while the 50s are a different beast altogether. No, what makes something inherently Disney is not if it follows a certain structure or has stock characters, it’s more about an ineffable mixture of charm, heart and wonder, where animation is used to explain whatever the mind can conceive. Tangled achieves this, even if at first glance it seems entirely different to, say, the Aristocats, Cinderella or Bambi.

Initially, the signs aren’t especially promising. The film opens with a witty voiceover that, while rather funny, represents a modern aversion to sincerity that has plagued post-Pixar animations. After a nice bit of scene-setting exposition to establish the main plot – girl with magical hair is trapped in a tower by a woman who pretends to be her mum – it then breaks into a song about how this lady of shallot wants to leave her tower. It’s a forgettable song, doing the bare essentials of revealing character motivation. She plays with a chameleon, Pascal, who is clearly there to sell toys (Pascal reaction shots are rather overused in the film as a shortcut to cuteness/humour that quickly becomes wearying). It all feels a little perfunctory, and it isn’t until she actually leaves her tower, accompanied by the caddish rogue Flynn Rider, that the film kicks off and becomes interesting.

The banter between the two companions is not only genuinely funny, but at times hints a thematic depth that Disney only achieves at their best. The comic highlight of the film is when Rapunzel first leaves the tower and it cuts between her having the best day of her life and wracked with guilt at what she has done to her mother. Mother Gothel, like Scar, get into the psyche of the victim, making Rapunzel blame herself even when the older woman is the kidnapper, manipulator and jailor. Like Elsa in Frozen, Tangled‘s heroine has a moment of breaking free of the rules, but unlike Elsa, Rapunzel feels conflicted about it. Her restoration to her proper family is not just about becoming a princess but is a process of self-actualisation, where she works out who she is as a person separate from the controlling influences of an older generation. In short, when Rapunzel leaves her tower, Tangled actually becomes about something, as opposed to just another princess story.

(As a side note, I think that’s why I didn’t like Cinderella as much as other princess films, because it wasn’t about anything. The best princess movies use the age old structure to explore a broad theme: Beauty and the Beast is about sacrifice; Mulan is about gender roles (broadly); Tangled is about freedom. Cinderella is just about a ball and dresses and half-talking mice.)

Having explored such weighty themes in the first act, the film transforms when the young princess enters her home town and enjoys life among normal people for the first time. There’s a montage after her hair has been tied up where she starts a dance in the town square, paints, reads books and just enjoys freedom – it’s where the film stops being good and becomes great. What makes this scene so special is that actually, you’ve seen similar sequences several times before, because the film makers are tapping into an age old tradition of falling-in-love montages. Such is the exuberance and unabashed enthusiasm of the scene that there is maybe something there that wasn’t there before. Rapunzel has the (frankly unbelievable) infectious happiness that can get a whole town dancing, twirling and laughing together, and it’s a joy to watch. It’s the culmination of her gradual emancipation, a scene that combines romance with personal freedom. I know I’m prone to hyperbole, but to me personally this scene touches the transcendent.

The film then segues into the breathtaking sight of a thousand lanterns floating through the sky to a generic ballad which, song aside, is beautiful. Neither the romantic lanterns scene nor the dance in the town are especially new or groundbreaking, but fitting into a grand Disney tradition of heartfelt romance and gorgeous animation. Yes, the film ends with the exact ending that you are expecting, but that’s the appeal of Tangled and, indeed, most of the Disneys: it’s escapism in its purest form, a tale of magic, royalty and once-upon-a-times. It’s a fairy tale.

Tangled revels in royalty and romance and is perhaps even more old-school than the traditionally animated Princess and the Frog. It follows a familiar narrative but the familiarity is warm and happy as opposed to cliché-bordering boredom. As such, Tangled could be described as run-of-the-mill for Disney, but only if the mill is a gorgeous, riverside waterwheel and cottage that happens to produce the finest flour in the country; It’s par for the course, but the course is a stunning mountain highway. It’s Disney through and through, which is why children and adults are bound to fall for its immense charm and will still be watching it in twenty or thirty years time.

The Princess and the Frog is the greatest Disney film of the 21st Century.

I was tempted to leave it at that, to just let that comment linger and pass it off as my article for the studio’s 49th film. A controversial statement, perhaps, but what could possibly top it? Tangled fans are probably already in uproar by this point and a few people would probably make a solid case for Frozen or Lilo and Stitch. Apart from these, however, no other Disney film can stake a legitimate claim to that title. The 21st Century had undoubtedly been a dry spell for the studio up until this point but far from being the best of a bad bunch, Princess is a league above everything that had preceded it since the millennium, a creatively, artistically superior product on just about every level. Yes, it functions as a breath of fresh air for a moribund department, but even removed from its historical context (were that possible), Princess stands shoulder to shoulder with some of the A-list Disneys. Flawed, admittedly, but then so were some of the mid-90s films, or the works of Wolfgang Reitherman or even, whisper it, the Golden Age films.

However, bunch of grumpy cynics that that critics are, not many people seemed to get this when the film was released. Glasgow Evening Times critic Paul Greenwood was lukewarm, saying that “the story is one of the weakest elements here… the swampy ragtime vibe is atmospherically realised, but the film never quite develops its own personality,” and he wasn’t alone. Peter Bradshaw at the Guardian arbitrarily compared it to Toy Story, saying it wasn’t as good, representing an utterly pointless trend of comparing the film to Pixar. Because critics were getting used to the gimmicky archness of the studio behind Cars 2, anything that dared to be sincere was treated with suspicion, as if everyone reviewing the film forgot that in a time before Toy Story they, too, fell in love with the traditional Disneys of their generation. The Pixar comparisons further underserve the film as the two studios are trying totally different things, they just both happen to be animated. No critic would make such arbitrary comparisons in live action, suggesting that some writers forgot that animation is a medium, not a genre. Anyway, what this ranting boils down to is that critics accused The Princess and the Frog of being derivative, lacking in magic and invention and out of place in the world of modern animation. They were very, very wrong.

The old school, traditional form of storytelling is precisely the appeal, however, so to dismiss it on those grounds misses both the charm of something sincere in a cynical world, but also the way that it actually progresses the princess formula while sticking fairly rigidly to it. It’s a film that unashamedly has romance, magic and villainy coursing through the film, unafraid of sentimentality and a good old fashioned happy ending, but it does it all with a irresistible vibrancy that makes it a good deal more appealing than something like Cinderella. Yes, it follows trajectories that audiences are familiar with (although more on why that isn’t entirely true in a bit), but it excels in every area as opposed to just ticking boxes.

Take, for instance, the bad guy. Villains don’t come much darker than Dr. Facilier, a voodoo doctor who calls up demonic shadows from his ‘friends on the other side.’ He’s a fantastic, terrifying creation, with a song and grisly demise that ranks among the most memorable in the studio canon. The animators use the look and movement of Facilier to make him unforgettably sinister; with a waist as thin as his pencil moustache and a head of floppy, uncombed hair, he seems to defy physics in the way he slinks from scene to scene, followed by a shadow that moves to its own rhythm. He looks and acts fearsome, but it turns out his power is beholden to even darker forces. He frequently reveals that he is more in danger than anyone else in the film, something which is graphically made real as he is dragged off to hell by his so called ‘friends.’ Needless to say, children of a sensitive disposition may be better off with Winnie the Pooh.

The animation and the songs, too, show the artistry that belies the claims that this is a derivative film. Randy Newman is the man behind the lyrics, but by setting it in Jazz era New Orleans, the stage is set for Disney’s most energetic, lively soundtrack featuring the husky voice of Dr John. Leaving behind the broadway ballads of the 90s, The Princess and the Frog utilises its setting and voice cast to great effect, so even when there isn’t a song being sung it still moves along to a toe-tapping rhythm. Unlike Hercules, the music is entirely congruent with the setting, too: it actually makes sense, here, to have a gospel number. Then there is the animation, which really could have an entire article devoted to it but I’ve already rambled at length about my love of traditional techniques. Needless to say they are given a glorious final gleaming, here, the mansions and swamps of Louisiana rendered in a humid pallet of greens and browns, occasionally glimmering gold, as well, suggesting that magic hangs thickly in the air there. It’s a beautiful, old fashioned animation and a testament to the beauty of hand drawn techniques. It should never have left Disney.

So even if its traditional techniques were all done to the highest standard, even within this structure The Princess and the Frog progresses the old fashioned princess narrative in a way that few give it credit for. Take, for instance, the opening scene in which Tiana and her friend Charlotte discuss fairy tales. Charlotte, a comic highlight throughout the film, expresses her desire to marry a prince. With bright, blue eyes, blond hair, a wealthy background and a penchant for royalty, she fits the Disney princess mould perfectly. However it is Tiana, who couldn’t care less about Princes but wants to run a restaurant, that is the film’s main character, not Charlotte. The colour of her skin is irrelevant – Disney have had non-white princesses since the 90s – but her attitudes and motivations are the noticeably different aspects about this heroine. Throughout the film she is motivated by her desire to run a restaurant and bring people together with her food. As a result, Prince Naveen is the first one of the couple to fall in love, and Tiana has to catch up. He has to win her affections, as opposed to her giddily falling in love the moment she meets him, a la Snow White. It also undermines a second Disney trope, that of wishing on a star, by balancing it with the importance of hard work – magic must be combined with a realistic work ethic.

Yet Tiana still ends up married, wealthy and human again, which perhaps serves to undermine the formula-breaking feistiness she has previously displayed. If hard work is more important than wishing on stars and handsome princes, why is it so important for her to end up with her prince and dreams coming true? Well, it’s a bit much for us to expect the people that directed The Little Mermaid to turn into animated Ken Loaches. Instead, it combines the independence and strength of Tiana with a bit of good old fashioned magic to ensure that the ending is more or less what you are expecting. However, the restaurant building is still bought with Tiana’s savings and ultimately Tiana realises the importance of love in the midst of her business ventures. It takes a callous heart to deny her marriage just because it’s unfeminist. Anyway, in this case the emphasis is not on romantic love, but familial, as Tiana wants to emulate her father, who was a family man above all. So it manages to update many of the tropes of a princess film, but does so maintaining the heart and sincerity of even their most traditional films. The Princess and the Frog miraculously manages to shift the dynamics of a princess narrative to something more palatable to modern audiences, while still revelling in the magic that such stories offer. It has its cake, and eats it.

As I mentioned at the beginning, the film is, of course, flawed. Cajun firefly Ray smacks of sidekick overkill and vague racial stereotyping, while his song and the whole ‘Evangeline’ thread of the film feel tacked on and irrelevant. An encounter with some frog eating swamp-dwellers, while amusing, feels similarly out of place and suspiciously like plot padding. It also verges a little bit on the cruel in its treatment of them as two fingered, stupid inbred hicks, although it does mine laughs from these rather crass stereotypes. But this is the kind of nitpicking that misses the bigger picture, and it’s easy to forget that Snow White – which still ranks as a masterpiece for me – features a painfully dull lead character, while Fantasia has sequences that go on for far too long and the Reitherman films all repeat themselves (a complaint levelled against Princess but rarely an issue with the 70s films). Yes, it’s not perfect, but it is damn near close.

In fact, you could say that it is the greatest Disney film of the 21st Century.

The Incredibles is a great film. It pokes fun at superhero films while managing to be a really good superhero film itself. Toy Story is a great film. It’s about someone who thinks he is more special than he actually is and has to come to the realisation that he is far more normal than being a super spaceman. Bolt is not a great film. It pokes fun at superhero films but isn’t really one itself, preferring instead to have a road trip where the main character discovers himself. It’s about someone who thinks he is more special than he actually is and has to come to the realisation that he is far more normal than being a super dog, although at the end he might as well have superpowers so it is all undermined anyway. Mostly it isn’t great because it’s trying too hard to be The Incredibles and Toy Story.

The Incredibles is a great film. It pokes fun at superhero films while managing to be a really good superhero film itself. Toy Story is a great film. It’s about someone who thinks he is more special than he actually is and has to come to the realisation that he is far more normal than being a super spaceman. Bolt is not a great film. It pokes fun at superhero films but isn’t really one itself, preferring instead to have a road trip where the main character discovers himself. It’s about someone who thinks he is more special than he actually is and has to come to the realisation that he is far more normal than being a super dog, although at the end he might as well have superpowers so it is all undermined anyway. Mostly it isn’t great because it’s trying too hard to be The Incredibles and Toy Story.

Still trying to work out what Disney should look like in the 21st Century, the battle between old and new continued with Bolt, which veered firmly the way of Pixar in an anti-Disney move, but ended up being nothing like a Disney film and only a pale reflection of the studio it was trying to emulate. In playground terms, it’s the malcoordinated nerd who can speak elvish trying to play American football in order to fit in with the jocks, but although he has the right kit he can’t find a position to play in on the team. In a desperate attempt to be cool, he just shows up everything he is not.

For starts, Bolt is based on a really contrived concept, about a dog who plays a superhero in a TV show that is specifically orchestrated so that he remains convinced that everything that happens is real. Even an audience with the most willing suspension of disbelief (and I count myself in that happily oblivious group) could find holes to poke in this premise, like who on earth would fund a show so ridiculously expensive (ok, kids probably don’t care about TV funding)? Or why does it only matter that the dog goes method, and not any of the human cast? Perhaps such Truman Show shenanigans would be too cruel if done to people in a kid’s film. Either way, it’s a very roundabout way of setting up the plot, which involves the dog travelling across the States to try and find his owner again, all while going on a journey of self discovery. By the time the plot begins, the audience is bored.

Then there is the tonal awkwardness of the film, as it opens with a cutesy dog home scene before an intentionally over-the-top action sequence as the central premise is introduced. There are explosions, super speed, laser eyes – things that are never explained in their ‘real world’ context – as Bolt fights baddies to rescue his owner. It goes on for aaaages, an interminable cacophony of bright, glossy animation and loud noises. Ultimately, it’s pointless, as the rug is pulled and the fabrication of the whole sequence is revealed; a nifty trick if the first sequence hadn’t been so long and convoluted. As it is, you are just left wondering what it was all for (the answer: nothing). Then it becomes a genial, villain-free, fish out of water road movie as Bolt accompanies as sassy New York cat and a naive hamster across the states. This section tries to establish a theme of abandonment issues – negated because we know that Bolt’s owner is desperate to get him back – and some awkward buddy comedy as the mismatched travelling companions roam the country. The hyperbolic opening is forgotten in favour of something much gentler but irredeemably bland.

This is no Chicken Little (to me a byword for substandard ’00s Disney), and contains a couple of exciting-ish set pieces and some nice jokes. The latter is provided mostly by Rhino, a hamster who believes everything he sees on TV. His moment of glory when they get back to the TV set is a genuinely funny moment in a film painfully lacking in laughs. The animation is also a few steps forward from Robinsons and Little, but it’s still uncannily cold. Children will probably be amused by this film, with its accessible themes and big action scenes, but adults may struggle to be as entertained.

The ultimate issue is that Disney just don’t tell stories like this. Wreck-It Ralph, although considerably more successful, suffered the similar problem of a studio trying to be who they were not. What that film got right was that it kept in a tangible emotional core, which this loses in favour of spectacle. Interestingly, the message of Bolt could be translated as, ‘don’t try to be something you are not,’ a message which Disney would do well to pay heed to.

SPOILER ALERT FROM THE START

Time travel is a funny old thing. There’s a moment in Meet the Robinsons where the main character is almost adopted by his future wife and it’s just a bit weird. The ramifications of all the time travel shenanigans in Disney’s sparky, enjoyable sci-fi are the kind that make your head hurt and cause you to question whether it all made sense in the first place. For instance – and this will only make any sense if you have seen the film – if older Goob had never met younger Goob and told him to be bitter would any of this have happened? But how would older Goob have known to be bitter in the first place in order to tell his younger self to remain that way? How come the exact same version of the future is restored after Lewis fixes everything (with some additions) given the chaos theory that the rest of the film seems to have employed? Surely the very act of meeting himself would cause a gigantic shift in the makeup of the world he visits?

Time travel is a funny old thing. There’s a moment in Meet the Robinsons where the main character is almost adopted by his future wife and it’s just a bit weird. The ramifications of all the time travel shenanigans in Disney’s sparky, enjoyable sci-fi are the kind that make your head hurt and cause you to question whether it all made sense in the first place. For instance – and this will only make any sense if you have seen the film – if older Goob had never met younger Goob and told him to be bitter would any of this have happened? But how would older Goob have known to be bitter in the first place in order to tell his younger self to remain that way? How come the exact same version of the future is restored after Lewis fixes everything (with some additions) given the chaos theory that the rest of the film seems to have employed? Surely the very act of meeting himself would cause a gigantic shift in the makeup of the world he visits?

Not everything seems to have been thought through here, but then the same accusation can be levelled at excellent time travel films like Back to the Future and Looper. When time travel is thought through too much, you get irredeemably boring films like Primer. Time travel films have to be taken with a generous pinch of salt and a healthy suspension of disbelief and if you ignore the questions raised by the dubious teleological mechanics of the plot then Robinsons is a whole lot of fun. The fact that these questions are being raised in the first place demonstrates that it is the most narratively ambitious film in the canon yet, a smart story that aims for Pixar and just about hits it. It is rather telling, then, that this is the first Disney film with John Lasseter as the creative head of animation.

This ambition makes for a film that is almost breathless in its execution, zipping at a considerable pace through the main events of the story. Opening on a rainy night in some nondescript American city, an anxious mother leaves her son on the steps of an orphanage before fleeing at a noise. From there the young Lewis’ abandonment issues and love of invention are quickly established, before he is whisked into the future and meets a family with a surname you can probably guess. It’s so speedy that you barely stop to think about the narrative inconsistencies and that’s the point; this is sharp yet silly fun from a studio that had, for several years by this point, been severely lacking it. There’s also an unusually ambiguous ending as the identity of that mother in the rain is never established, which leaves the film with a peculiarly melancholic aftertaste that the makers of Chicken Little would never dare to attempt.

Thematically it’s slightly immature but it marks a giant step forward from the facile daddy issues of their last film. Both the hero and villain are orphans, a quick shortcut to emotional problems and themes of isolation, abandonment and family. Lewis’ desire to belong to something feels familiar, but it is balanced nicely by the theme of failure as a necessity in success. The biggest appeal of the future family is that they celebrate his failure as a step on the road to success. It’s a celebration of human invention and progress that lands an unexpectedly emotional punch with a closing tribute to Walt Disney, who inspired the central motto of the film: Keep Moving Forward.

After a few films of languishing in the doldrums of mediocrity and after the atrocious Chicken Little, Meet the Robinsons marks the start of a new era for Disney that combines wit and ideas as well as classier, smoother animation to convey them. Lasseter’s contribution was a lifeline to a struggling studio and Robinsons pleasingly hints that the once great House of Mouse was still capable of brilliance.

“I’m yet to see Chicken Little, Home On The Range or Meet the Robinsons, but it is unlikely that any of them will feel as rote or humdrum as this sub par effort.” So I foolishly said about Treasure Planet, a film which, with the hindsight that Chicken Little affords, comes across as a masterpiece of Golden Age proportions compared to this CG sci-fi dreck. The absolute nadir of ’00s Disney, it is currently threatening Saludos Amigos for the claim to ‘worst in the canon.’ Maybe because it’s come after a long run of mediocrity so it was simply frustrating to witness yet another less-than-spectacular film, or maybe because it is a genuinely dreadful film. Either way I hated it.

“I’m yet to see Chicken Little, Home On The Range or Meet the Robinsons, but it is unlikely that any of them will feel as rote or humdrum as this sub par effort.” So I foolishly said about Treasure Planet, a film which, with the hindsight that Chicken Little affords, comes across as a masterpiece of Golden Age proportions compared to this CG sci-fi dreck. The absolute nadir of ’00s Disney, it is currently threatening Saludos Amigos for the claim to ‘worst in the canon.’ Maybe because it’s come after a long run of mediocrity so it was simply frustrating to witness yet another less-than-spectacular film, or maybe because it is a genuinely dreadful film. Either way I hated it.

Structurally, it’s all over the place. The first act of the film consists entirely of the titular poultry basically being a loser to a soft-rock soundtrack before acts two and three become an alien invasion film. The theory being, supposedly, that the central dynamic between rooster and son should be established before the main ‘plot’ kicks in, but the execution suggests that everyone involved is far more interested in the aliens than in a young chicken trying to reconnect with his father who is (rightly) embarrassed by his son. The first act, therefore, feels completely extraneous and incongruous with the rest of the film, containing an entire arc for the main character that turns out to be completely unnecessary to the rest of the film. Chicken Little’s foray into baseball is utterly, utterly pointless. The rest is hardly interesting, too.

Then there is the humour, which tries to be a bit knowing and meta but fails to actually be funny. The film opens with the narrator unsure of how to start the story, going through a few clichés before just starting at the beginning. Such jokes are nice if the rest of the film is going to be a self referential deconstruction of Disney tropes, á la Enchanted, but it isn’t, so the opening feels like a studio desperately trying to capture some of the wit (and box office) of Shrek. It’s worthless poking fun at clichés in the first 5 minutes if the ensuing 75 are full of them. Then occasionally throughout the rest of the film it remembers that it wants to be arch and witty so makes an arbitrary reference to something like King Kong. A clever pastiche of Hollywoodising true stories at the very end of the film is the only joke that really registers, but it is far too little, far too late.

The sci-fi elements of the film are underdeveloped, a far cry from the likes of Lilo and Stitch which used its genre setting to great effect. The aliens are (perhaps deliberately) generic and no thought has gone into the design of the ships or creatures. The ‘twist’ at the end is mildly unexpected but undermines anything that has gone before and doesn’t make a whole lot of sense given the apparent desire for violence shown earlier in the film. The design is weak, the story weaker, adding to a litany of laziness that amounts to a whole lot of boredom when watching the finished product.

Then there is the animation. Sweet mother of mercy, the animation. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, made 68 years before this abomination, was using technology that was still in its infancy. The people working on it were still discovering how it worked, no one was sure if the film would be a success or not, yet the result was triumphant and it still looks good today. Chicken Little was made using technology that had successfully been the medium of feature length films for 10 years but was still, granted, a fairly new innovation. Today it is one of the ugliest films ever made, only 8 years old now but horrendously dated to the extent that it is almost unwatchable. Blocky, textureless characters and flat, detail deprived landscapes add up to a thoroughly unappealing aesthetic that looks like a gifted 14 year old has taught himself computer animation. Think Spyro the Dragon on PS1 or Jimmy Neutron on an off day. Every single frame should be destroyed and we should probably forget that this film ever happened.

With this underwhelming, slightly strange critter Western, the death knell for traditional animation at the House of Mouse pealed across the land. While the studio resurrected the medium for two more films, they were but the final, beautiful throes of a whole department about to enter a state of rigor mortis. This was the film where they decided to leave 2D behind for good – Princess and Winnie the Pooh were afterthoughts. If Home on the Range is where it came to die, Chicken Little is the ugly xenomorph that burst from it in death. Maybe if this half hearted Western had been a little bit better then hand drawn films would have stood a chance. As it is, this article is more an announcement of a death than a review. The Princess and the Frog will be my eulogy.

With this underwhelming, slightly strange critter Western, the death knell for traditional animation at the House of Mouse pealed across the land. While the studio resurrected the medium for two more films, they were but the final, beautiful throes of a whole department about to enter a state of rigor mortis. This was the film where they decided to leave 2D behind for good – Princess and Winnie the Pooh were afterthoughts. If Home on the Range is where it came to die, Chicken Little is the ugly xenomorph that burst from it in death. Maybe if this half hearted Western had been a little bit better then hand drawn films would have stood a chance. As it is, this article is more an announcement of a death than a review. The Princess and the Frog will be my eulogy.

If this all sounds a little macabre and morose it’s because I got confused and accidentally watched this and Chicken Little out of order and the latter film has the honour of being one of the worst films in the canon. As I saw it, I wondered why Disney were so determined to leave one medium behind to replace it with something that was, at the time, underdeveloped and just plain ugly. It made me want to root for Home on the Range so it could be celebrated as the triumphant last hurrah of cels before the march of coded progress trampled it beneath its glossy, soulless feet. Alas, it was not to be. Instead of going out in a blaze of glory, 2D died with a wheeze of half remembered beauty.

Attempting a Western for the first time since the package films of the Forgotten Forties, Home on the Range tells the forgettable story of three cows who want to save their beautiful dairy farm from a villainous land-grabbing cattle rustler. Japes ensue. Taking more of a road-movie adventure approach in the style of The Rescuers Down Under or (sort of) Dinosaur, the structure is undermined by the fact that every new place they encounter looks exactly the same as the last. Films about journeys, especially animated ones, work well when it opens up the creative team to explore different locales. As it is, Home on the Range is merely a tramp through various different versions of one boring desert.

Perhaps the strangest choice made in the film is the voice cast, which features Judi Dench (as a cow in the deserts of the US?), Roseanne Barr and Cuba Gooding Jr. Each one of them voices their character like they are in different films to everyone else, an uncertainty which is carried over into the haywire tone of the film. At times it’s a slapstick comedy, at others a heartwarming ‘Save the Farm’ drama. At one point it features an utterly bizarre technicolour trip of a musical interlude that once more feels as though it has wandered in from another film (or even studio). None of these elements are particularly bad but they don’t gel as a whole, resulting in a film that feels uncertain of itself and never hitting the heights it is aiming for.

This last gasp of traditional animation from Disney suffers from the studio’s determination in the ’00s to try something different and leave behind old stories with princesses and magic. When it works, it works well, as with Lilo and Stitch and The Emperor’s New Groove. However when they pushed this desire for difference too far, Disney forgot what made them great in the first place: beautiful animation; enchanting story telling; a big, beating heart beneath it all. Home on the Range is torn between the draw of modernity and a dying medium and the result is something that, while diverting and occasionally funny, fails to register on most levels. It is representative of a studio having an identity crisis and it came at the cost of hand drawn animation, which is a lamentable shame.

With the Disney 52 reaching a conclusion that will inevitably be rushed, the powerhouse studio scupper my plans by releasing their 53rd animated feature film, Frozen. So in the middle of reviewing the latter films, I’m jumping ahead a few years to look at this immensely popular new film from the studio. It feels a bit defunct to try and assess its place within the canon as there are still a few I’m left to see. As such you won’t find any ‘the best Disney film since The Lion King/Snow White/Tangled style comments here – besides, I’ve enjoyed all of Disney’s most recent films so it wouldn’t go back far. I’m just pleased not that Disney are returning to form, but maintaining it.

Frozen tells the story of two sisters, Elsa and Ana, who are separated as children after Elsa accidentally injures her sister with her magic, ice creating powers, so she is sectioned off until she can control them. After their parents’ tragic death Elsa becomes Queen, but after Ana falls in love with the dashing Hans of the Southern Isles quite hastily, Elsa reveals her powers and casts the nation into deep winter. Ana must then go and persuade her sister to bring summer back. It’s (extremely) loosely inspired by Hans Christian Andersen’s the Snow Queen, but Disney have bigger fish to freeze than faithfully adapting the writer of The Little Mermaid once more.

Immediately Frozen establishes the central dynamic of the film as between the two sisters as opposed to between a man and woman. After an eerie, largely pointless opening about how great and dangerous ice is it cuts to Elsa and Ana as children, seeing their friendship play out before they are separated. The second song in a Disney film is often the one that reveals the central desire of the hero – think ‘Part of Your World,’ ‘Go The Distance,’ or ‘Reflections’. At first glance it may seem like that role is given to the third song in Frozen – ‘For The First Time In Forever’ is about how lonely Ana is and wants to meet people and, specifically, a man. It’s the kind of Disney song that would normally be the ‘hero’s desire’ song. The second song, however, is actually more fitting: ‘Do You Wanna Build A Snowman’ is about how Ana longs for a relationship with her sister. From the off, other relationships are secondary and so it is in the rest of the film where Ana’s romantic confusion is superseded by her love of her sister. It builds to a fascinating, dramatic finale that marks a noteworthy change of direction for a studio usually obsessed with romantic love, particularly in fairy tale settings.

With the focus on the siblings, the role of villain becomes less clear as well – is it Elsa? The Duke of Weseltown? The ice itself? Elsa battles with her dark side and – in the musical highlight of the film – almost succumbs to it, which is a refreshingly mature exploration of character for Disney. Obviously it is done in a way in which everything is spelt out for the young audience, but the tension between good and evil has become significantly more nuanced since the days of the Golden Age, as has the approach to romance, which similarly undergoes a knowing face-lift. On most narrative fronts, Frozen take significant steps forward for the studio.

It’s a shame, therefore, that it falls into some age old traps that have plagued the House of Mouse since day one. The female characters, whilst interestingly written, are still waistless waifs with big eyes, so generically fake that one wonders if they have used the exact same model for both sisters that was previously employed for Tangled. If Disney really want sassy, revisionist Princesses their next step is surely to animate some that look like humans. Then there is the Duke of Weseltown who is utterly extraneous to plot or theme, harking back to Disney’s occasional need to overfill a film with characters. Sven the reindeer, meanwhile, is just Maximus with antlers, leading some to say that Disney are resting on their Tangled laurels and that this film is simply par for the course.

Such accusers must be ignoring not only the steps forward with storytelling that Frozen takes, but also the artistry with which the story is told. Musically, Frozen is Disney’s most Broadway film yet thanks to songs by the people behind Avenue Q and The Book of Mormon. Vocals cross over each other, high notes are hit and there is even a comic song that doesn’t add anything to the plot. The cast, too, are veterans of the proscenium arch, featuring actors from Wicked, Spring Awakening and The Book of Mormon, belting the songs out with remarkable conviction. Even the way the shots are framed and the characters move feels ready-made to be put on the stage. It wouldn’t be surprising if a big budget production makes its way to New York in the near future.

Then there is the animation, which I’ve left until last because it’s probably the thing that most people care least about in terms of what makes it good, but I geeked out about in a big way. The texture of the snow itself is ludicrously detailed to the extent that you can see individual grains as the characters plough through it. Compare the fineness of detail here to the blockiness of landscapes in something like Ice Age and the difference in quality is immediately evident. It’s so good it will make animation nerds cry a little. If you didn’t notice how good the animation was that’s because they made it all seem so effortless.

Frozen is the real deal, featuring progress in storytelling, astonishing animation and great songs. It’s the best Disney film since…

This review is only turning up online after the film in question has left cinemas, but I thought I would very quickly share my two cents on it as that was the original purpose of the blog – to review animations that make it into cinemas. This isn’t really a review, just a jumbled collection of thoughts as I focus on finishing a certain project before January 1st.

The first Cloudy With A Chance of Meatballs film was an unexpected delight, blending puns, surrealism, slapstick and farce into one memorable comedy, throwing every joke possible at the screen and most of it stuck like well cooked spaghetti. Even the title was a great joke. This was combined with a father-son story that was more effective than most, and a nicely offbeat, colourful aesthetic. I’d personally rank it as one of my favourite CG animations. The news of a sequel was initially ominous as the title – simply sticking a ‘2’ at the end – seemed to display a lack of thought behind it. When plot details were revealed it became clear that the title didn’t even make sense in a new context. Add to that the fact that Phil Lord and Chris Miller were no longer directing and the signs were bad.

Thankfully, however, Cloudy 2 manages to be one of the best American animations of the year that, while immensely derivative of the first film, still succeeds at being one of the most consistently hilarious things to hit cinemas 2013. It loses some of the layers of humour from the first – it’s less farcical and surreal – but ups the ante in terms of puns and visual humour to compensate. The father-son subplot feels like a rehash of the first, but the visuals are once again good enough to make you immensely hungry. It also aims for a whole new level of cuteness, clearly skewing at a younger audience than the first with its smiling strawberries and baby marshmallows. So it’s not quite as good as the first, as suggested by the title, but it is hilarious.

The chief joy of Cloudy 2 is the way it turns punning into an art form. Any combination of food/animal names possible turns up over the course of the film, some spoken out loud, others left for the audience to guess. There’s one sublime moment, however, that builds up these expectations of intelligent(ish) puns before letting you down with a sad looking vegetable – it’s the kind of joke that I’ve left deliberately vague in the explanation as it requires the visuals to make you snort out your soft drink. The funniest moment in the film, however, is a glorious visual gag that involves a wide shot as Sam Sparks leaves Flint behind in a swamp of syrup. It’s daft but inspired, like the film as a whole. With all of these jokes, explaining it is pointless (making comedy really hard to write about), just go in expecting to have your gut busted. It really is funny, even if I’m not selling it as such.

One final thought – Cloudy 2 features a clear villainous Steve Jobs type figure and a giant, invention-crushing corporation not too dissimilar to Apple. It feels, at times, like Cloudy 2 is trying to fit in a bit of satire and critique of globalism and capitalism in amongst the feast of jokes. When you come for tasty humour, such moralising is bitter to swallow.

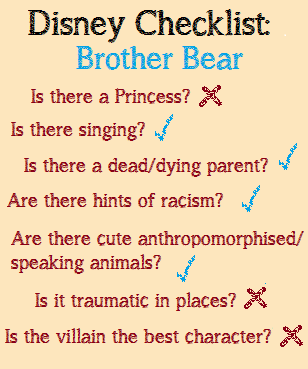

Phil Collins is, of course, a musical genius. Anyone who has seen Tarzan can attest to this incontrovertible fact. Lyrically, musically, emotionally, spiritually, he hit all the right levels and I am not exaggerating for an instant when I say that. However, even Einstein had his off days, so it is with a heavy heart that I write about Brother Bear’s biggest problem: Phil Collins. The Genesis front man and modern day Bach was called up to write the songs for Disney’s Canadian legend about a boy who becomes a man by becoming a bear. Only something must have gone wrong along the way because the resulting soundtrack is so painfully on-the-nose that it feels like he just sang the synopsis of the film. There’s actually a point in the film when there is a big emotional reveal and the two main characters confront some brutal truths. Just as they begin discussing such a problematic issue as matricide, ol’ Phil kicks in with an earnest melody that actually includes the lyric ‘brother bear…’

Phil Collins is, of course, a musical genius. Anyone who has seen Tarzan can attest to this incontrovertible fact. Lyrically, musically, emotionally, spiritually, he hit all the right levels and I am not exaggerating for an instant when I say that. However, even Einstein had his off days, so it is with a heavy heart that I write about Brother Bear’s biggest problem: Phil Collins. The Genesis front man and modern day Bach was called up to write the songs for Disney’s Canadian legend about a boy who becomes a man by becoming a bear. Only something must have gone wrong along the way because the resulting soundtrack is so painfully on-the-nose that it feels like he just sang the synopsis of the film. There’s actually a point in the film when there is a big emotional reveal and the two main characters confront some brutal truths. Just as they begin discussing such a problematic issue as matricide, ol’ Phil kicks in with an earnest melody that actually includes the lyric ‘brother bear…’

I‘m getting ahead of myself. Let’s go back to the beginning and discuss the plot and positives of Brother Bear. A young inuit named Kenai is disappointed when he is told that his life’s totem and dominating characteristic that will make him a man is… love. He doesn’t display this love when he goes on a revenge killing and murders a bear. The great spirits who watch over everything then decide that he should pay for his crime by turning him into a bear himself. Once ursine, he has to look after a little cub, Koda, and try and reach the place where the lights touch the earth so he can be returned to two legged, fleshy form. Bonding happens along the way, moose are canadian, and there’s fish out of water humour in literal and figurative senses.

The biggest positive is, naturally, the animation. Even on their off days, Disney could pull out fairly magnificent looking films and given dramatic Canadian landscapes to work with, the Brother Bear team excel. There’s an interesting, largely unnecessary choice made by the directors to change the aspect ratio and colour scheme once Kenai becomes a bear. Presumably it’s related to the fact that now he can see more clearly, but it’s a welcome change as the film becomes breathtaking in widescreen. It’s the best looking Disney film since Tarzan. It’s also regularly funny and, in the credits ‘outtakes’ has the best laugh in any Disney film, ever.

But the problem is that the plot and ‘message’ of the film are hammered home with about as much subtlety as being mauled by a bear. The film starts off with a song about how the great spirits unite all creatures of the earth in one great big circle of life family. This apparent hymn to vegetarianism seems an oddly patronising and culturally suspect song to sing about a group of hunter-gatherers, however spiritual they may or may not have been. Then once Kenai is transformed, he has to learn to love others, particularly the immensely annoying Koda. His journey feels painfully obvious, but the pseudo-spirituality of the film particularly grates as it brings back unwelcome memories of Pocahontas. There’s nothing quite as annoying as the magic leaves, here, but it has a similar sense of ignorance and Hollywoodisation of complex beliefs.

To cap this all off, there’s Phil’s song lyrics coursing throughout with such painful writing as ‘This is our festival / you know and best of all / We’re here to share it all’ to induce winces in audiences all around the world. The themes of family, love and peace are so broad and movieish that when hammered home by Phil – who was clearly writing these on a day off – it becomes an endurance test as to how long you can sit through the songs before getting out your copy of Tarzan. On a positive note, Mr. Collins also wrote the score to the film with Mark Mancina, and that’s actually great. Even in his darkest hour, Sir Phil is still a talented son of a gun.

Sandwiched, as it is, by some of the worst films in the Disney canon, Brother Bear actually comes out looking pretty good. It’s beautifully animated, very funny and largely entertaining. You just wish it was a bit more subtle, which is saying something when talking about a Disney film…