Imagine The Third Man without that iconic zither accompanying the fractured angles and chiaroscuro that make up the visuals. Contemplate a version of The Good, The Bad and the Ugly where the Mexican stand-off at the end doesn’t have a single note of Ennio Morricone‘s jangling, nervy score. Since the advent of synchronised sound, non diegetic music (that is, any music that is not within the world of the film, so no CDs being played or on screen bands) has been an integral part of what makes a film work. Arguably animation has been at the forefront of combining sound and visuals for a holistic cinematic experience. Steamboat Willie was pioneering in its perfect synchronisation of image and sound, and to this day ‘Mickey mousing’ is a term used when the film’s score directly represents the action on screen, for example someone tip-toeing would be heard as a high pitched notes on a xylophone. Most Disney films are great to just listen to, as well as to look at.

Imagine The Third Man without that iconic zither accompanying the fractured angles and chiaroscuro that make up the visuals. Contemplate a version of The Good, The Bad and the Ugly where the Mexican stand-off at the end doesn’t have a single note of Ennio Morricone‘s jangling, nervy score. Since the advent of synchronised sound, non diegetic music (that is, any music that is not within the world of the film, so no CDs being played or on screen bands) has been an integral part of what makes a film work. Arguably animation has been at the forefront of combining sound and visuals for a holistic cinematic experience. Steamboat Willie was pioneering in its perfect synchronisation of image and sound, and to this day ‘Mickey mousing’ is a term used when the film’s score directly represents the action on screen, for example someone tip-toeing would be heard as a high pitched notes on a xylophone. Most Disney films are great to just listen to, as well as to look at.

When the studio started out, some of their best shorts were the Silly Symphonies, a group of stories inspired by and told to pieces of music. Here, the music plays an even bigger part of the film – instead of complimenting the pictures, it defines them. Their first feature films used sound to a considerable extent: in Bambi the music floats by like the wind; Snow White has the iconic song Hi-Ho as well as a regal, fairy tale score. Fantasia, meanwhile, was one long tribute to classical music, a collection of artistic interpretations of Bach, Beethoven et al. It was Silly Symphonies transformed into high art, where music became bursts of colour, epic battles between heaven and hell and the foundation of the world itself. It was a near perfect representation of how music could inform and inspire the visual elements of a film.

Make Mine Music is like the more rebellious but less talented younger brother of Fantasia; he’s the member of the family that would much rather listen to contemporary music than classical, but has no real appreciation of great music. That’s not to say Make Mine Music is a bad film – it’s a bit like comparing an amateur jazz musician to his older brother, the child prodigy Juilliard scholar. Happily, in fact, Make Mine Music is a whole lot of fun and a refreshing departure from the awful trip to South America experienced in Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros. There are moments of real brilliance, here, even if the film as a whole lacks the impact and grandeur of Fantasia.

Based on the same idea as Fantasia, this rejects the big names of the earlier film in favour of contemporary music; you’ll find no Schubert here. The result is something that feels very much of its time, but struggles to break out of its rather dated confines to become something more enduring and memorable. Much of the music feels rather dreary, especially the opening skit ‘Blue Bayou’ which, as the name suggests, is about a cobalt coloured swamp inhabited by a lonely stork. The animation is an immediate improvement on the first two films of the Forgotten Forties, but it feels a little maudlin. It’s pretty, but forgettable. Then all of a sudden, it ends, and the next sequence begins. The biggest bonus of using contemporary songs is that they are a whole lot shorter than a classical movement, and so the film zips along at a right old pace. If you don’t like one of the scenes, it doesn’t matter because it will be over soon. Such speedy transition between the sequences makes this instantly far more enjoyable than either of the preceding films from this period.

The second huge advantage of using contemporary music is that in the 1940s that included jazz. The free-wheeling spirit of that era gives many of the sequences a really lively, vibrant atmosphere. One of the highlights is ‘All the Cats Join In,’ a wonderfully peppy interlude where a group of teenagers (a new phenomenon at this time) dance together to the syncopated rhythms of the title song. It takes place in a sketch book, so the characters look like they have walked right out of an Archie comic, and the backgrounds are just blank colours, giving a greater focus to the movement of the dance. This skit also contains one of my favourite ideas in animation: the intervening animator. The action is drawn as it happens, making it unpredictable and fresh, and makes the best use of a lower budget in a way that Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros failed to do.

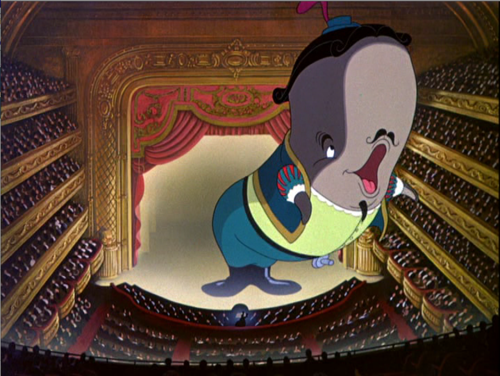

Make Mine Music also rediscovers Disney’s storytelling abilities that had been lost so far in the Forgotten Forties. What made Fantasia so great is that each piece of music was brought to life by really memorable, entertaining stories. This film shares some of that DNA, and whilst a few of the stories are not especially strong (there’s a hilariously sexist bit about baseball), such weaker moments are balanced by segments such as Disney’s interpretation of Prokofiev’s famous ‘Peter and the Wolf’, which brings new life to the famous music and features a terrifying wolf. The best of the stories is probably ‘The Whale Who Wanted to Sing At the Met’, a funny, entertaining story of an operatically talented Cetacean with big dreams that fully redeems whales in my eyes after the horror that was Pinocchio. What stands out most about this tale is the ending, which is wholly unexpected and leaves the film on a far more bittersweet note than you might anticipate. The fear in ‘Peter and the Wolf’ and the emotions of ‘The Whale…’ display Disney’s capacity to get an audience invested in a story, something which has been sorely lacking in this period.

Yet just like Fantasia, Make Mine Music is not afraid of the abstract as well as the more straightforward stories. Some of the best music evokes something inexpressible in us, and the animators are careful not to render everything too literally. There’s nothing quite as dizzyingly beautiful as the ‘Toccata and Fugue’ in Fantasia, but this does contain some evocative, inventive imagery, such as a willow drooping in the snow turning into a cathedral or instruments and sheet music coming to life. The animation still hasn’t reached the heights of their first five films, as it’s still just a bit too simple and childish to truly impress, but this shows a good deal more imagination and flair than has so far been evident in the period since Bambi. That’s representative of the film as whole; there is a long way to go before they hit the dizzy heights of the Golden Age, but this is a marked improvement on their South American films.

With Make Mine Music, Disney appear to have their verve back. It’s not a perfect film by any stretch, but it’s fast and fun enough to make it a thoroughly enjoyable 80 minutes. Disney show, yet again, that music can inspire creativity and beauty in cinema. As with all portmanteau films not every section is equally strong, but this is nevertheless a film that features a whale that can sing opera and a love story between two hats. It’s very difficult to be too negative about that.

tt

U do know that there is actually another segment before blue bayou? It was cut for violence, but I think it starts the film better than blue bayou. Ilu should check it out in YouTube. Called ‘martin and the coy’ I think….